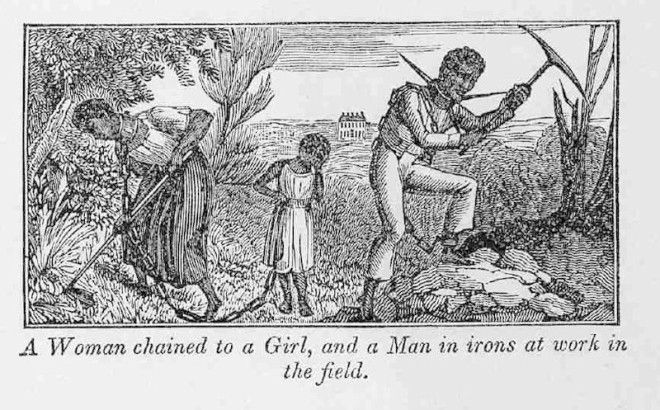

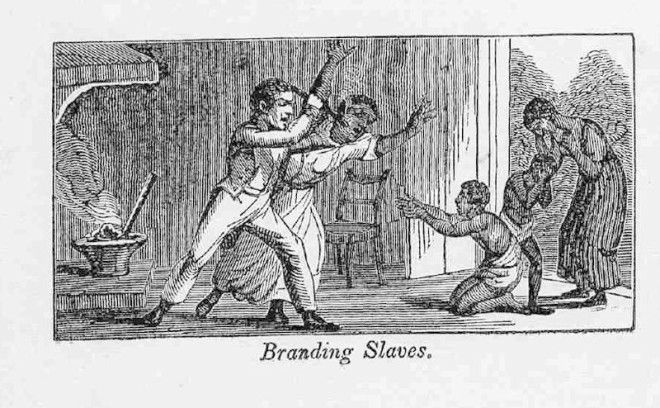

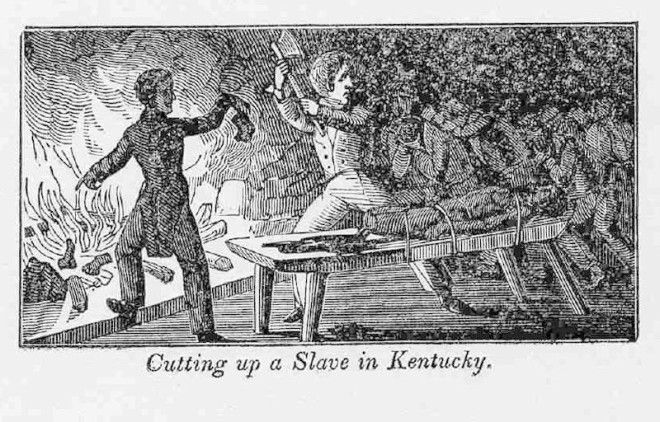

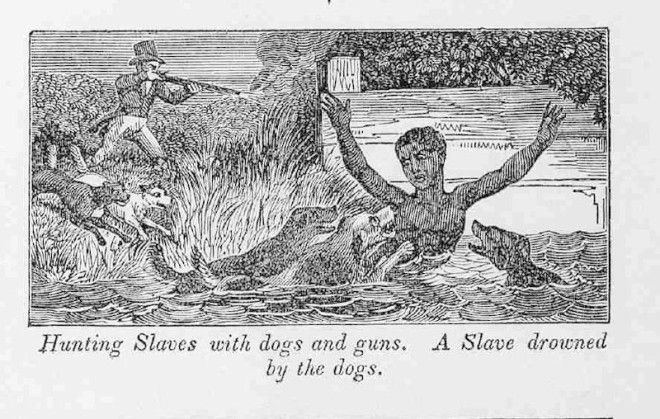

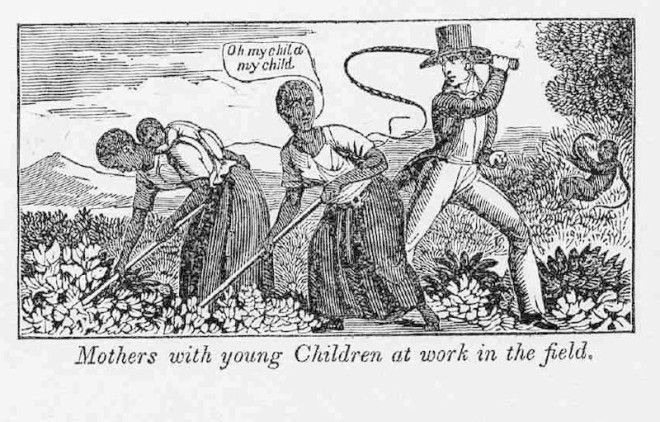

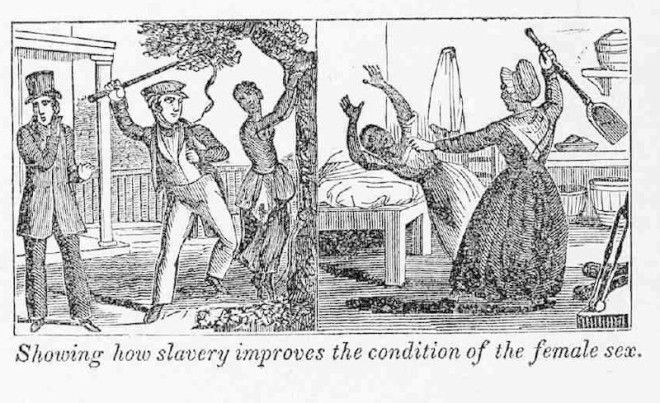

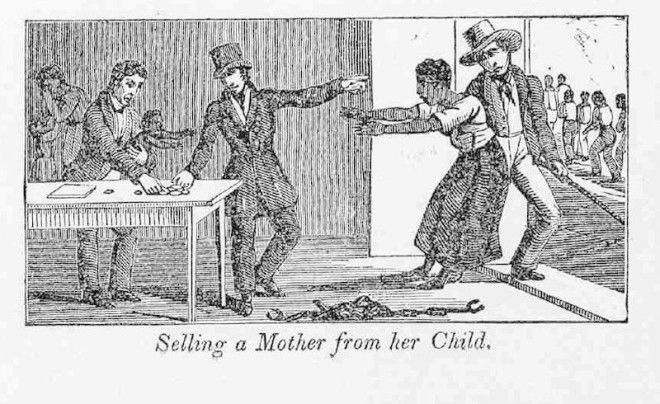

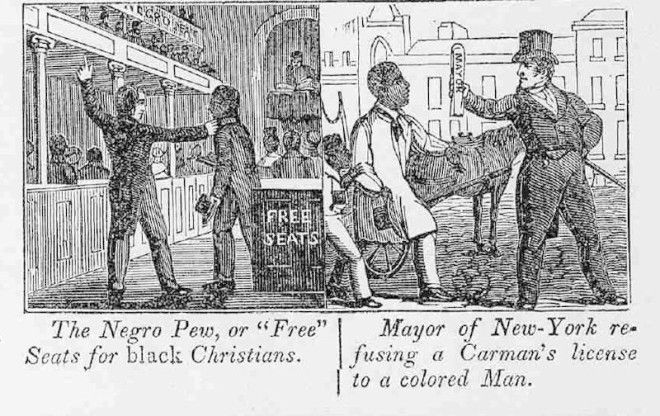

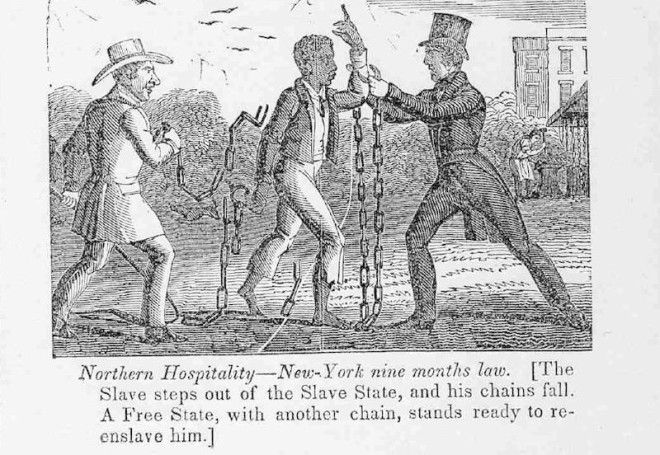

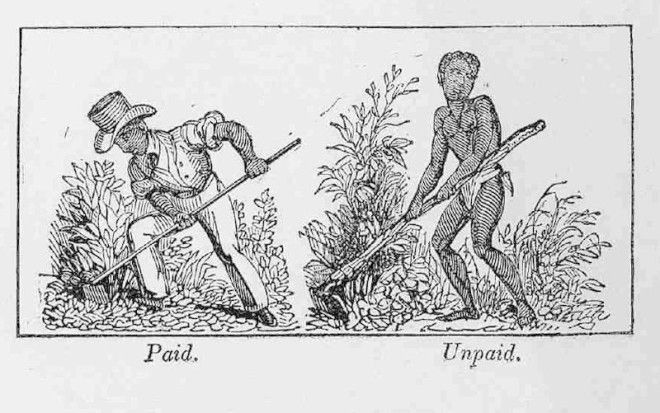

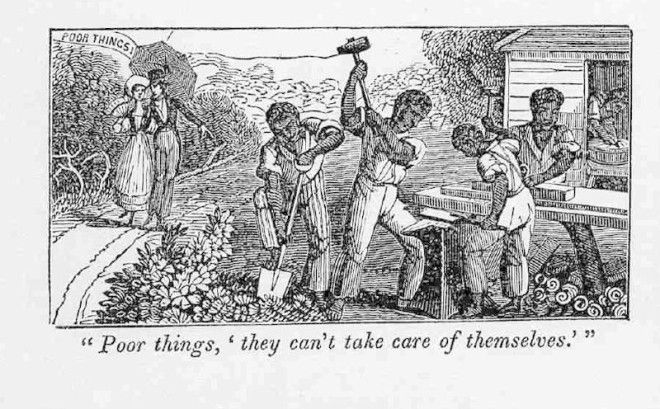

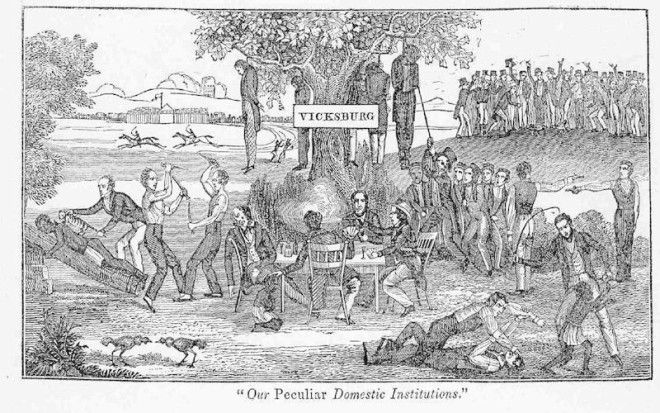

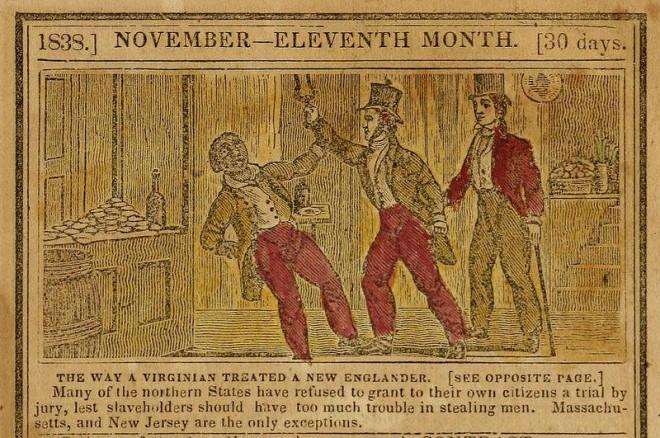

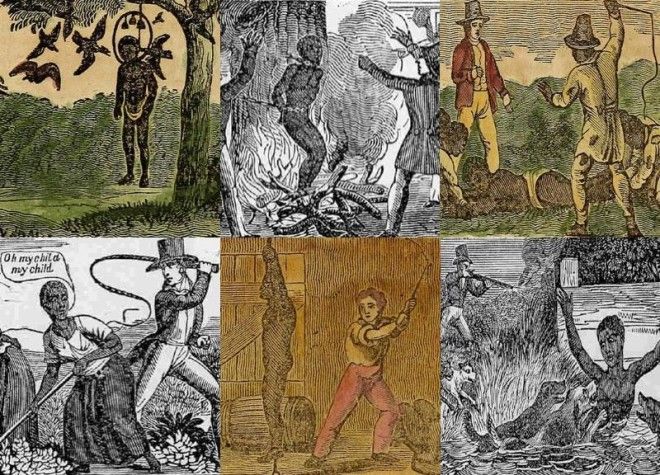

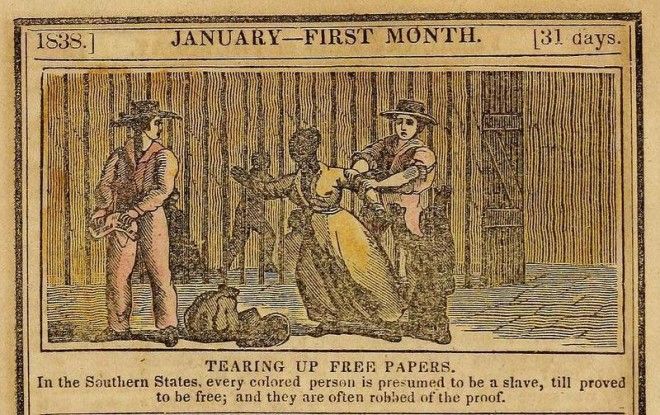

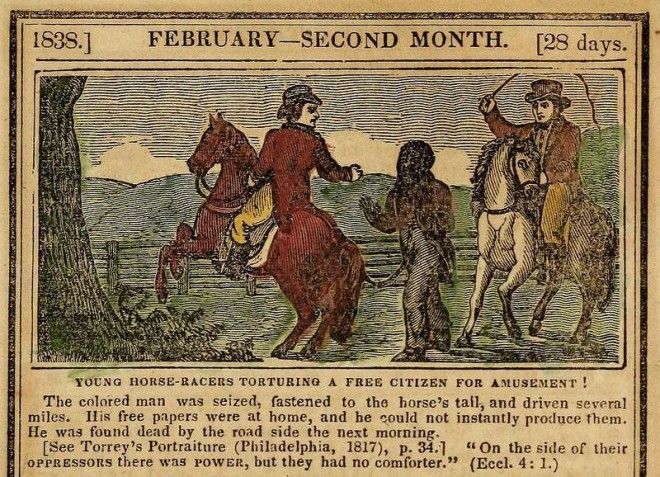

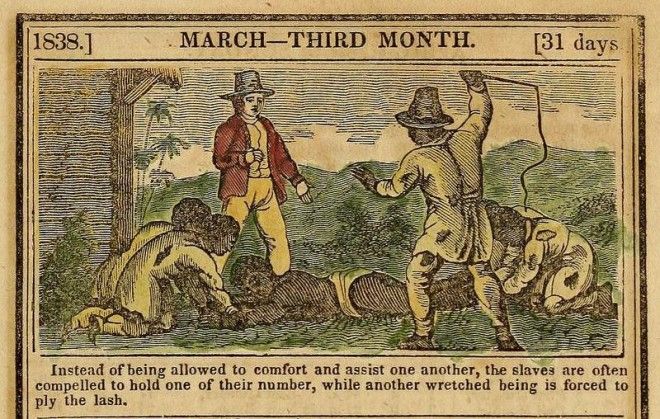

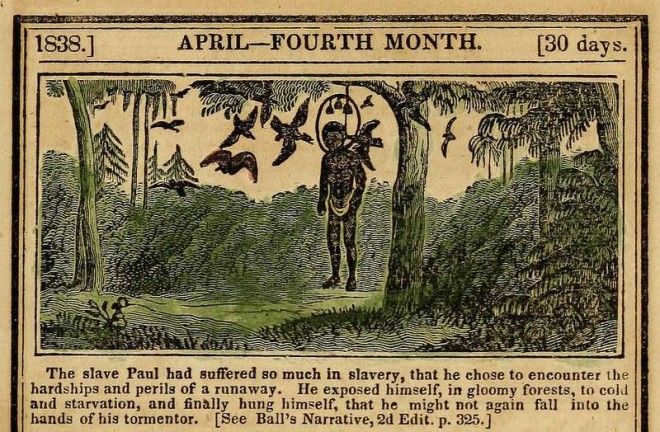

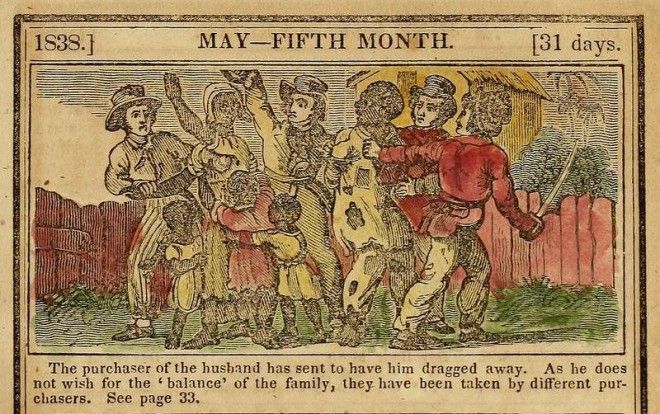

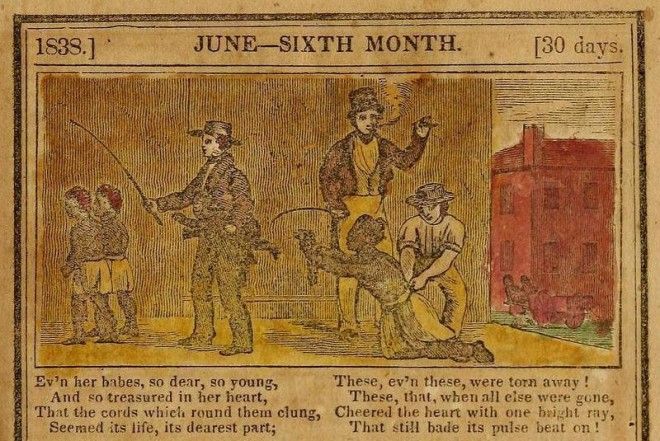

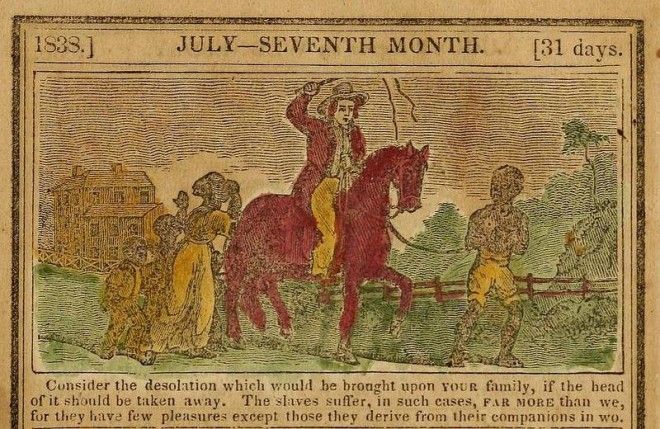

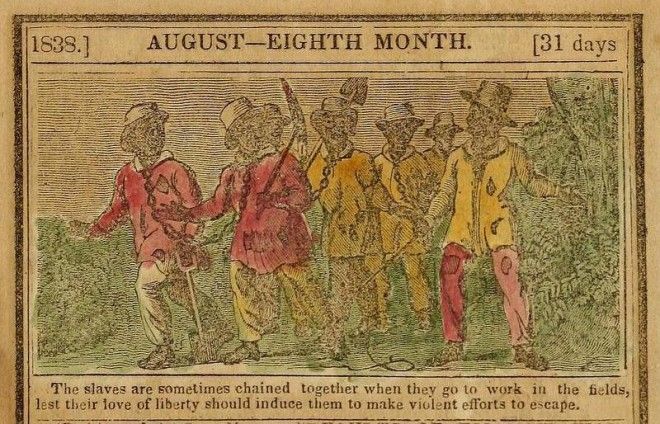

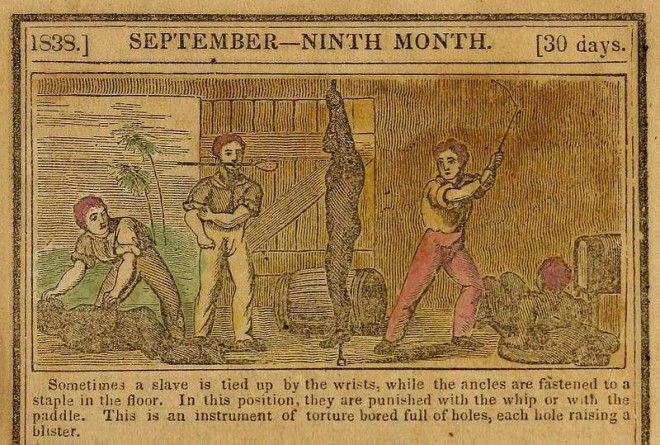

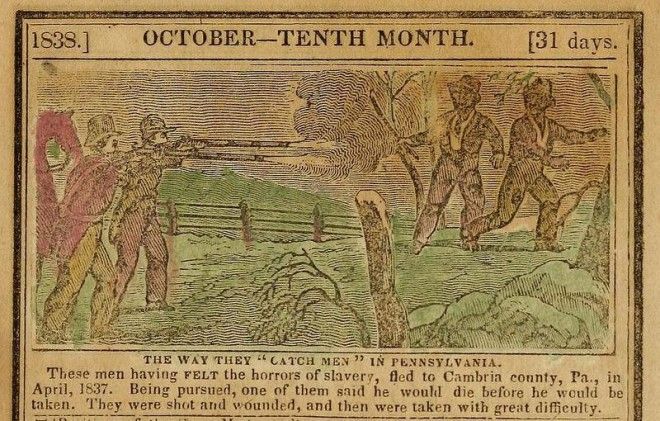

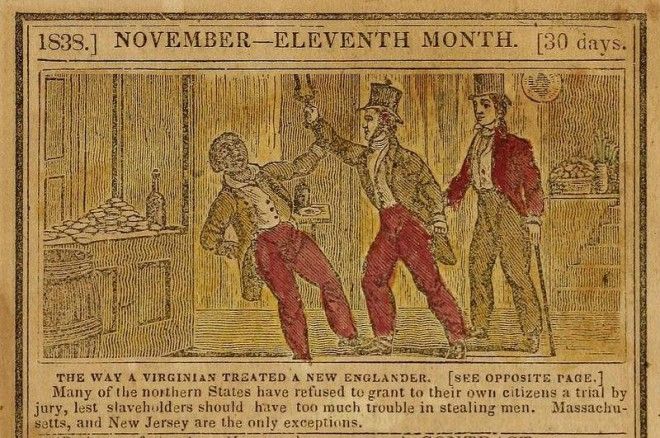

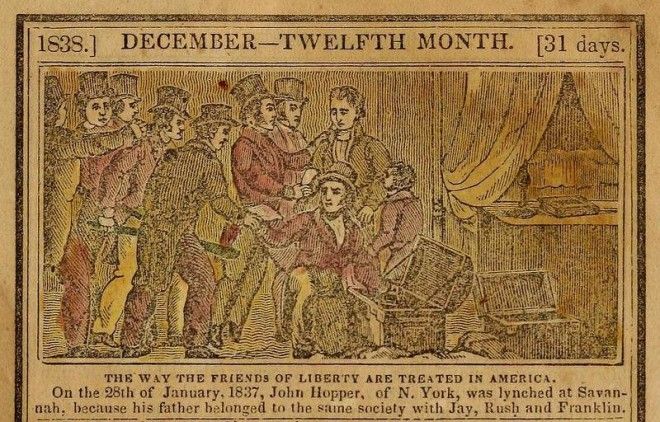

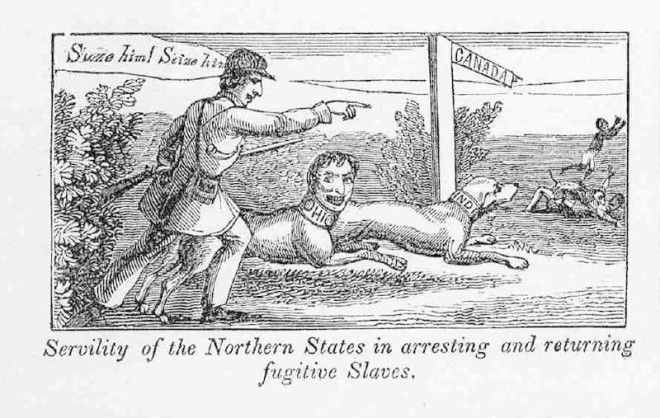

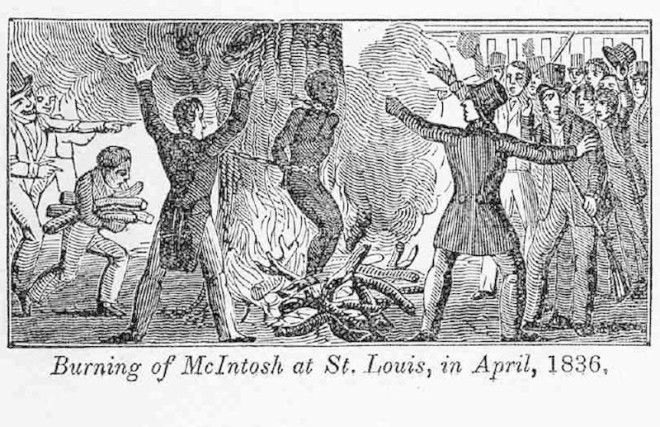

When the American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS) published the first Anti-Slavery Almanac in 1836 (and for years after that), they sought to educate people on the moral and ethical horrors of slavery, and included graphic images of slaves’ treatment to emphasize the un-Christian nature of the practice. As you’d imagine, these images created quite the controversy:

Advertising