1. THE BALD EAGLE

For much of the twentieth century, this American icon was in jeopardy. Habitat loss, overhunting, and the widespread use of DDT—an insecticide which weakens avian eggshells—once took a major toll on bald eagles. By 1963, the species population in the lower 48 states had fallen from an estimated 100,000 individuals to just 417 wild pairs. To turn things around, the U.S. government passed a series of laws, including a 1973 ban on DDT that was implemented by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). These efforts paid off; today, approximately 10,000 wild breeding pairs are soaring around in the lower 48.

2. THE ARABIAN ORYX

The Arabian oryx is a kind of desert antelope indigenous to the Middle East. Reckless hunting devastated the species, which became essentially extinct in the wild during the early 1970s. However, a few individual animals were still alive and well in captivity. So, in the 1980s, American zoos joined forces with conservationists in Jordan to launch a massive breeding program. Thanks to their efforts, the oryx was successfully reintroduced to the Arabian Peninsula, where over 1000 wild specimens now roam (with a captive population of about 7000).

3. THE GRAY WOLF

Even well-known conservationists like Theodore Roosevelt used to vilify America’s wolves. Decades of bounty programs intended to cut their numbers down to size worked all too well; by 1965, only 300 gray wolves remained in the lower 48 states, and those survivors were all confined to remote portions of Michigan and Minnesota. Later, the Endangered Species Act enabled the canids to bounce back in a big way. Nowadays, 5500 of them roam the contiguous states.

4. THE BROWN PELICAN

Louisiana’s state bird, the brown pelican, is another avian species that was brought to its knees by DDT. In 1938, a census reported that there were 500 pairs of them living within the Pelican State’s borders. But after farmers embraced DDT in the 1950s and 1960s, these once-common birds grew scarce. Things got so bad that, when a 1963 census was conducted, not a single brown pelican had been sighted anywhere in Louisiana. Fortunately, now that the era of DDT is over, the pelican’s back with a vengeance on the Gulf Coast and no longer considered endangered.

5. ROBBINS’ CINQUEFOIL

Noted for its yellow flowers, Robbins’ cinquefoil—or Potentilla robbinsiana—is an attractive, perennial plant that’s only found in New Hampshire’s White Mountains and Franconia Ridge. Collectors once harvested the cinquefoil in excessive numbers and careless backpackers trampled many more to death. In response, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service re-routed hiking trails away from the flower’s wild habitats. This, along with a breeding program, rescued the Robbins' cinquefoil from the brink of extinction.

6. THE AMERICAN ALLIGATOR

With its population sitting at an all-time low, the American alligator was recognized as an endangered species in 1967. Working together, the Fish and Wildlife Service and governments of the southern states the reptiles inhabit took a hard line against gator hunting while also keeping tabs on free-ranging communities. In 1987, it was announced that the species had made a full recovery.

7. THE NORTHERN ELEPHANT SEAL

Due to its oil-rich blubber, the northern elephant seal became a prime target for commercial hunters. By 1892, some people were beginning to assume that it had gone extinct. However, in 1910, it was discovered that a small group—consisting of less than 100 specimens—remained at large on Guadalupe Island. In 1922, Mexico turned the landmass into a government-protected biological preserve. From a place of security, that handful of pinnipeds bred like mad. Today, every single one of the 160,000 living northern elephant seals on planet Earth are that once-small group’s descendants.

8. THE HUMPBACK WHALE

Did you know that the world’s humpback whale population is divided into 14 geographically-defined segments? Well, it is—and in 2016, the National Ocean and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) informed the press that nine of those clusters are doing so well that they no longer require protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act. The cetaceans’ comeback is a huge win for the International Whaling Commission, which responded to dwindling humpback numbers by putting a ban on the hunting of this species in 1982. (That measure remains in effect.)

9. THE RED WOLF

After the red wolf was declared “endangered” in 1973, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service rounded up every wild member of the species they could find and put them all into captivity. By then, the canid’s formerly wide geographical range had been reduced to a small portion of coastal Texas and Louisiana. FWS officials only managed to locate 17 wolves—14 of whom helped kick off a successful breeding program. Meanwhile, the red wolf was declared extinct in the wild in 1980. But thanks to those original 14 animals, we now have a captive red wolf population of 200. The FWS has also used their stock to release additional wolves into national wildlife refuges.

10. THE WHITE RHINO

Make no mistake: The long-term survival of Earth’s largest living rhino is still very uncertain because poachers continue to slaughter them en masse. Nevertheless, there is some good news. Like black-footed ferrets and northern elephant seals, white rhinos were once presumed to be extinct. But in 1895, just under 100 of them were unexpectedly found in South Africa. Thanks to environmental regulations and breeding efforts, more than 20,000 are now at large.

11. THE WILD TURKEY

It’s hard to imagine that these poultry birds were ever in any real trouble, and yet they looked destined for extinction in the early 20th century. With no hunting regulations to protect them, and frontiersmen decimating their natural habitat, wild turkeys disappeared from several states. By the 1930s, there were reportedly less than 30,000 left in the American wilderness. Now, over 6 million are strutting around. So what changed? A combination of bag limits set by various agencies and an increase in available shrublands.

12. THE BLACK-FOOTED FERRET

North America’s only indigenous ferret is a prairie dog-eater that was written off as “extinct” in 1979. But the story of this animal took a surprising twist two years later, when a Wyoming pooch gave a freshly-dead one to its owner. Amazed by the canine’s find, naturalists soon located a wild colony. Some of these ferrets were then inducted into a breeding program, which helped bring the species’ total population up to over 1000.

13. THE CALIFORNIA CONDOR

Since 1987, the total number of California condors has gone up from 27 birds to about 450, with roughly 270 of those being wild animals. With its 10-foot wingspan, this is the largest flying land bird in North America.

14. THE GOLDEN LION TAMARIN

A flashy, orange primate from Brazil’s Atlantic Forest, the golden lion tamarin has been struggling to cope with habitat destruction. The species hit rock-bottom in the early 1970s, when fewer than 200 remained in the wild. A helping hand came from the combined efforts of Brazil’s government, the World Wildlife Federation, public charities, and 150 zoos around the world. There’s now a healthy population of captive tamarins tended to by zookeepers all over the globe. Meanwhile, breeding, relocation, and reintroduction campaigns have increased the number of wild specimens to around 1700—although urban sprawl could threaten the species with another setback. But at least the animal doesn’t have a PR problem: Golden lion tamarins are so well-liked that the image of one appears on a Brazilian banknote.

15. THE ISLAND NIGHT LIZARD

Native to three of California’s Channel Islands, this omnivorous, four-inch reptile was granted federal protection under the Endangered Species Act in 1977. The designation couldn’t have come at a better time, as introduced goats and pigs were decimating the night lizard’s wild habitat in those days. But now that wild plants have been reestablished under FWS guidance, more than 21 million of the reptiles are believed to be living on the islands.

16. THE OKARITO KIWI

Small, flightless, island birds usually don’t fare well when invasive predators arrive from overseas. (Just ask the dodo.) New Zealanders take great pride in the five kiwi species found exclusively in their country, including the Okarito kiwi, which is also known as the Okarito brown or rowi kiwi. These animals have historically suffered at the hands of introduced dogs and stoats. But recently, there’s been some cause for celebration. Although there were only about 150 Okarito kiwis left in the mid-1990s, conservation initiatives have triggered a minor population boom, with about 400 to 500 adult birds now wandering about—and that population is growing by two percent a year. Taking note of this trend, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has just declared that the Okarito kiwi is no longer endangered.

17. THE BROWN BEAR

Let’s clear something up: The famous grizzly bear technically isn’t its own species. Instead, it is a North American subspecies of the brown bear (Ursus arctos), which also lives in Eurasia. Still, grizzlies are worth mentioning here because of just how far they’ve come within the confines of Yellowstone National Park. In 1975, there were only 136 of them living inside the park. Today, approximately 700 of them call the place “home,” a turn of events that led to the delisting of Yellowstone’s grizzlies as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act earlier this year.

18. THE THERMAL WATER LILY

With pads that can be as tiny as one centimeter across, the thermal water lily is the world’s smallest water lily. Originally discovered in 1985, it was only known to grow in Mashyuza, Rwanda, where it grew in the damp mud surrounding the area’s hot spring. Or at least it did. The thermal water lily seems to have disappeared from its native range. Fortunately, before the species went extinct in the wild, some seeds and seedlings were sent to London’s Royal Botanic Gardens. There, horticulturalists figured out a way to make the lilies flower in captivity, and managed to saved the species.

19. THE PEREGRINE FALCON

When a peregrine falcon dives toward its airborne prey, the bird-eating raptor has been known to hit speeds of up to 242 miles per hour. The species endured a plummet of a different sort when DDT dropped America’s population. In the first few decades of the 20th century, there were around 3900 breeding pairs in the United States. By 1975, the number of known pairs had been whittled down to 324. Things got better after the insecticide was banned, and according to the FWS, somewhere between 2000 and 3000 peregrine falcon couples currently patrol the skies in the United States, Canada, and Mexico.

20. PRZEWALSKI’S HORSE

There are a few different subspecies of wild horse, all of which are endangered. One variant is the Przewalski’s horse (Equus ferus perzewalskii) from Mongolia. It completely vanished from that nation during the 1950s, but by then assorted zoos around the world had started breeding them. From 1992 to 2004, some 90 captive-born horses were released into Mongolia. They thrived and around 300 are living out there today.

21. THE NORTH AMERICAN BEAVER

No one knows how many of these buck-toothed rodents were living on the continent before European fur traders showed up. But after two centuries of over-trapping, incentivized by the lucrative pelt trade, the number of North American beavers had shrunk to an abysmal 100,000 in 1900. Their fortunes reversed when restocking programs were implemented in the U.S. and Canada. Nowadays, somewhere between 10 and 15 million beavers live in those countries. Given their landscaping talents, many property owners have come to see the furballs as pests.

22. THE CAFÉ MARRON

Rodrigues Island in the Indian Ocean once gave biologists a chance to raise the (near) dead. This landmass is the home of a small tree with star-shaped flowers called the café marron. It was thought that the plant had long since died out when a single specimen was found by a schoolboy named Hedley Manan in 1980. As the only surviving member of its species known to mankind, that lone plant assumed paramount importance. Cuttings from the isolated café marron were used to grow new trees at England’s Royal Botanical Gardens. Right now, there are more than 50 of these plants—and all of them can have their ancestry traced straight back to that one holdout tree.

23. THE WEST INDIAN MANATEE

A docile, slow-moving marine mammal with a taste for sea grasses, the Floridian subspecies of the West Indian manatee is a creature that does not react well to razor-sharp propellers. Collisions with boats are a significant threat, and the danger won’t go away altogether. Still, the passage of tighter boating regulations has helped the Sunshine State rejuvenate its manatee population, which has more than tripled since 1991.

24. THE BURMESE STAR TORTOISE

The pet trade did a number on these guys. Beginning in the 1990s, wildlife traffickers harvested Burmese star tortoises until they effectively became “ecologically extinct” in their native Myanmar. Luckily, conservationists had the foresight to set up breeding colonies with specimens who’d been confiscated from smugglers. The program started out with fewer than 200 tortoises in 2004; today, it has more than 14,000 of them. “Our ultimate objective is to have about 100,000 star tortoises in the wild,” Steve Platt, a herpetologist who’s been taking part in the initiative, said in a Wildlife Conservation Society video.

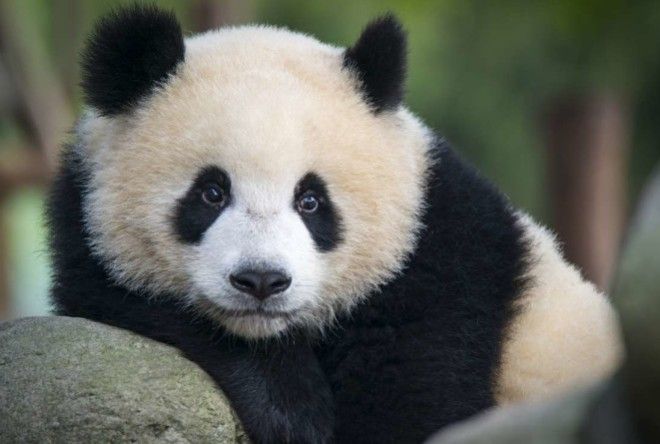

25. THE GIANT PANDA

Here we have it: the poster child for endangered animals everywhere … except that the giant panda is no longer endangered. Last year, the IUCN changed its status from “endangered” to “vulnerable.” There’s still a chance that we could lose the majestic bamboo-eater once and for all someday, but the last few years have offered a bit of hope. Between 2004 and 2014, the number of wild pandas saw a 17 percent increase. The welcome development was made possible by enacting a poaching ban and seeing an explosion of new panda reserves. It’s nice to know that, with the right environmental policies, we can make the future brighter for some of our fellow creatures.