For months, Colombo had waged war against the Paramount movie, asserting it propagated an exaggerated fiction about the existence of the mafia. Colombo had intimated there would be labor issues, production delays, and other, less defined obstacles that could threaten to curtail the studio’s multimillion investment in their adaption of Mario Puzo's 1969 novel. He could make such statements because, in addition to his real estate interests, Colombo was a major figure in organized crime.

Before Colombo could utter a word at the rally, a man disguised as a press photographer dropped his camera, raised a revolver, and shot Colombo three times in the head and neck. Colombo’s men immediately retaliated, shooting the assassin dead.

For Paramount, any sense of relief would be short-lived. In making sure nothing interrupted filming of The Godfather, producers had made a very public—and very costly—pact with the mob.

When prodded by reporters, the outspoken Colombo would deny there was any such thing as a mafia. “Mafia, what's a mafia?” he was once quotedas saying. “There is not a mafia. Am I head of a family? Yes. My wife and four sons and a daughter. That's my family.”

A cursory investigation of Colombo’s past would reveal otherwise. After commandeering the Profaci crime family in the mid-1960s, and capitalizing on the void left by incarcerated boss "Crazy" Joe Gallo, Colombo quickly rose through the ranks of New York’s notorious Five Families. He had been indicted for tax evasion and accused by the FBI of running a widespread gambling and extortion ring.

Most suspected criminals would keep a low profile. Instead, Colombo decided to go big. Co-creating the Italian-American Civil Rights League, Colombo decried sensational media stories regarding Italian-Americans in general. He found support in members of his ethnicity—nearly 45,000 members—who were tired of the stereotypes. An Alka-Seltzer commercial with the catchphrase “That’s-a-some-a-spicy meatball” was an early target, and the League had success getting it removed from the airwaves. He also lobbied to have the word “mafia” taken out of scripts for television’s The FBI.

In rallying law-abiding Italians and depicting himself as the aggrieved party, Colombo was successful in helping to stifle reference to the terms "mafia" or "la cosa nostra" in popular culture. As soon as Paramount announced plans to produce The Godfather, he had acquired his biggest target to date.

The film version of the Puzo novel had been brought to the studio by producer Robert Evans, who had acquired Puzo’s treatment in 1968. Puzo, heavily in debt due to a gambling habit, was eager to have the book and film rights erase his ledger. He openly admitted his research into organized crime was limited to asking questions of dealers and players during card games in casinos.

The Godfather sold 750,000 copies in hardcover and would go on to sell millions more in paperback. Because of the book’s success, the adaptation was heavily publicized before a single frame had been shot. When Colombo got wind of it, he made it known that the production would not be welcome in New York locations if it insisted on embracing stereotypes—a clever misdirection that helped take some attention off his own criminal doings.

Although Colombo never took credit for it, the film’s producer, Al Ruddy, began experiencing a series of unsettling events that seemed connected to the League’s public protests. His car windows were shot out; threatening phone calls came into his office. Strange cars followed him on the road. At Gulf & Western, Paramount’s parent corporation, phoned-in bomb threats evacuated the building twice.

Ruddy grew concerned, not only for his own welfare but for that of the picture. If Colombo wanted to disrupt the production by ordering Teamsters to sit idle or to arrange for scenery—or even actors—to come up missing, it would be disastrous.

Ruddy decided to capitulate. In early 1971, he arranged for a meeting with Joe Colombo and his son, Anthony, to discuss the picture. Ruddy handed them the 155-page script and insisted the film wouldn’t embrace the stereotypes the League was opposing.

Colombo was there to deal. He told Ruddy that if the filmmakers struck any mention of “mafia” or “la cosa nostra” from the script and donated proceeds from the movie’s premiere

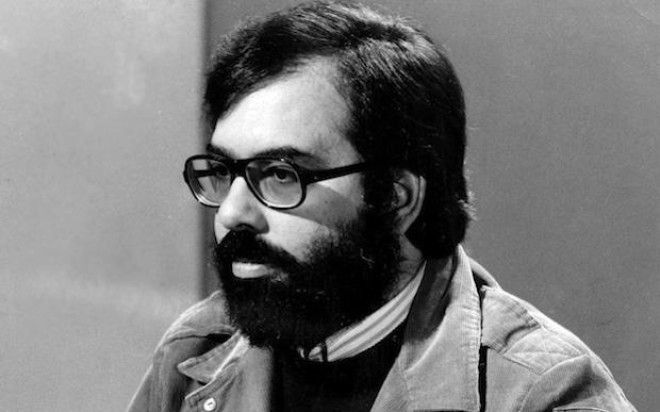

When executives at Gulf & Western learned Ruddy had essentially made a handshake deal with the mob, they were furious. Stock prices plummeted; Ruddy was called to the carpet and fired from the film, only to be rehired at Coppola's insistence.

If Colombo felt like a winner, it wouldn’t last long. His strategy of an aggressive defense may have won him small victories in the general public’s knowledge of the mafia, but it would cause a fatal reaction among those in organized crime who didn’t like Colombo’s profile.

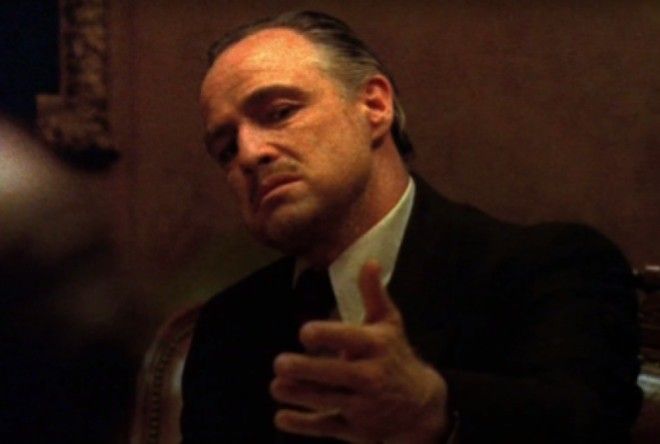

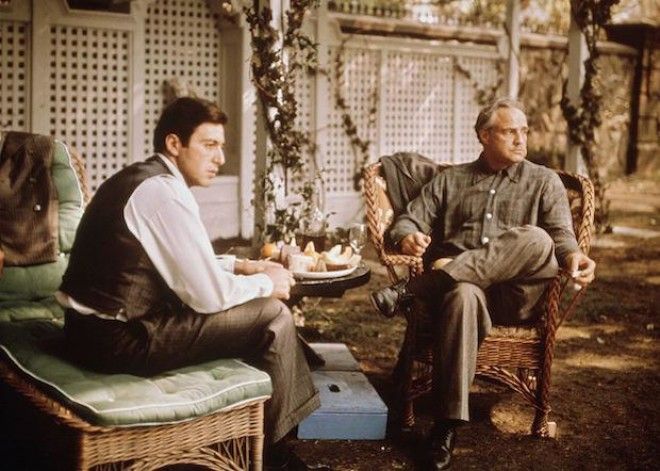

Months into shooting, Coppola had turned his attention from quieter scenes featuring family patriarch Don Corleone (Marlon Brando) to the bloodshed resulting from his assassination. On June 28 and 29, 1971, the director shot grisly scenes of mob hits featuring machine guns and squibs.

Four blocks away from the film’s location, Colombo had assembled a rally for an Italian-American Unity Day. As he moved to the podium, a photographer with a press pass named Jerome Johnson cut through the crowd and toward the stage. Before Colombo realized what was happening, Johnson had raised a gun and fired three shots, hitting Colombo in the head. More guns were drawn, and Johnson was shot dead on the spot.

Colombo was rushed to the hospital, but his injuries were severe. He spent the next seven years in a coma before passing away in 1978.

Although the murder was never officially solved, it was believed that a returning and vengeful Gallo, tired of Colombo’s grandstanding, ordered his rival’s demise. In what was thought to be a retaliatory attack, he was killed just one year later while eating at a restaurant for his birthday.

The murders were a surprise to Coppola, who had been concerned the violence depicted in the film might be outdated in what appeared to be a newer, more pacifistic organized crime landscape. When it opened in March 1972, The Godfather seemed more timely and prescient than ever.

Ruddy was unable to keep his promise to devote the premiere’s profits to the League, as Paramount refused to honor the deal. But he did host a private screening for the hundreds of limo-riding private citizens who expressed an interest in seeing the film in the New York area. They loved it and congratulated Ruddy on the accomplishment. Months prior, Ruddy had been forced to keep a .45 automatic gun in his desk drawer. It had been an uneasy, necessary alliance.

“Without the mafia’s help, it would’ve been impossible to make the picture,” Ruddy said.