Spanning as far back as the 15th century, the semi-nomadic eagle hunters — or bukitshi, as they are known in Kyrgyz — have used birds of prey to help capture foxes and hares in western Mongolia. Indeed, the much-feared Genghis Khan is believed to have had over 5,000 “eagle riders” in his personal guard. “Fine horses and fierce eagles are the wings of the Kazakhs,” one proverb goes.

But some fear that the Kazakhs are losing their wings. Over the past few decades, globalizing economies have worn down the tradition, increasingly drawing the young men who might otherwise participate in this rite of passage to urban spaces. Today, an estimated 250 bukitshi operate in western Mongolia, though some estimates have it as low as 50-60.

Where globalization and urbanization have called the future of the solitary hunt into question, to some Kazakhs they have also highlighted the importance of its preservation.

“They realized [the eagle hunting] is something they shouldn’t let die out,” Wolfgang Kaehler, an award-winning photographer who saw the eagle hunting for himself at last year’s Golden Eagle Festival, toldATI. “So every October they meet and have the festival, and it became popular.”

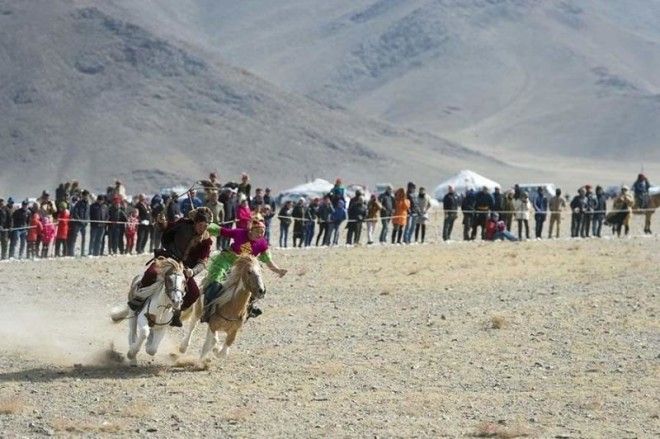

Some of Kaehler’s photos from last year’s festival — which has been in the running for over a decade and features several competitions such as traditional costume, horseback riding and eagle hunting — can be seen below:

A Kazakh eagle hunter showing off his golden eagle at the Golden Eagle Festival.

A group of Kazakh Eagle hunters and their golden eagles posing after arrival at the Golden Eagle Festival grounds.

A group of Kazakh Eagle hunters and their golden eagles arriving at the festival grounds.

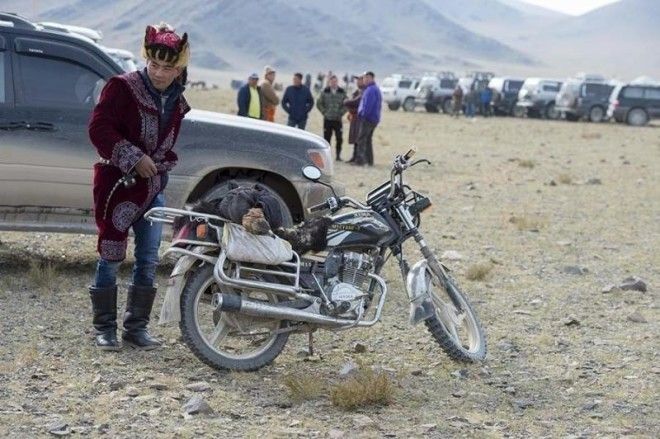

A Kazakh eagle hunter and his golden eagle arrive on motorbike.

A Kazakh eagle hunter with his golden eagle.

A Kazakh eagle hunter at the Golden Eagle Festival.

A tourist poses with a Kazakh eagle hunter and his golden eagle.

A group of Kazakh eagle hunters and their golden eagles arriving at the Golden Eagle Festival grounds.

That’s not to say that a desire for cultural survival means that the Kazakhs turn themselves into caricatures, though. “It’s a festival for them, really,” Kaehler said. “There’s really not that much infrastructure for tourists.”

Advertising

If Kaehler’s own experience at the Golden Eagle Festival is to serve as any kind of guide, this won’t be changing any time soon. During his five-night stay at a nearby campground, Kaehler recounted that he had no access to running water or toilets, an experience he said was echoed by a colleague who chose to stay at a hotel.

Indeed, those who do attend the Eagle Festival see the tradition, region and culture exactly as it is — often with, as Kaehler has experienced himself, wonder.

“It’s amazing,” Kaehler said. “You see these big birds that [the hunters] take when they’re small and train them, and then they’re released back in the wild so they can reproduce and have a normal life. It seems surprising that it works, but then you realize that the [eagles] are being trained for hunting, and it’s no wonder that they can survive.”

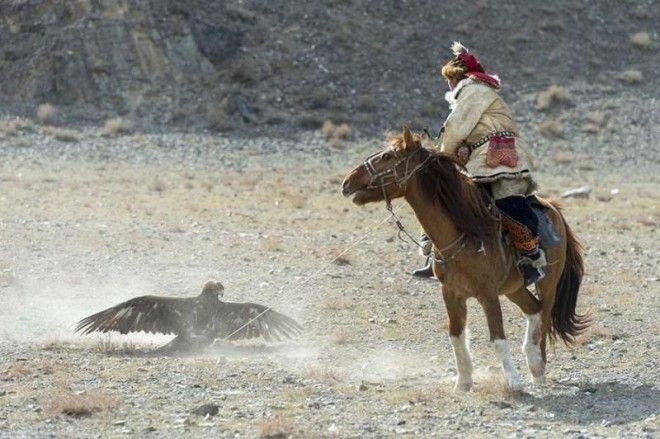

So just what does the festival’s signature eagle hunt look like? “It depends on the category,” Kaehler said. “In one, the eagle [is released from a hill] and has to land on the hunter’s hand, and since [it’s timed] the hunter is anxious to attract the eagle as soon as possible.”

In other competitions, Kaehler said, eagles must land in designated spots in a field, to which the hunters have to lure them with bait.

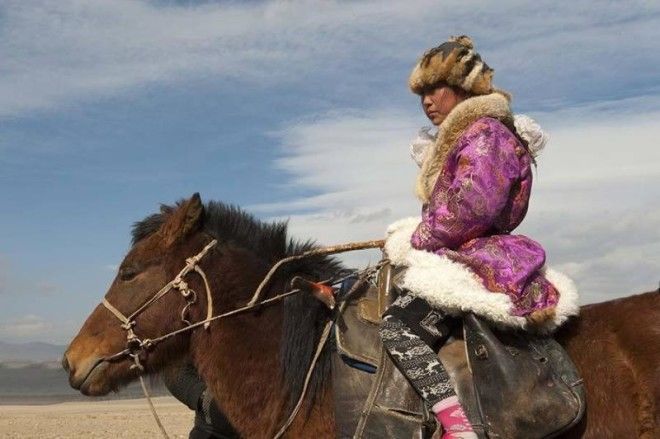

Kaehler has high hopes for the festival’s ability to preserve the tradition — and make it more inclusive. While eagle hunting is traditionally a rite of passage for young boys, “The [festival] now attracts younger people, even girls,” Kaehler said. “Two years ago, a young girl won.”

Portrait of a Kazakh teenage girl eagle hunter (winner of 2014 competition) at the Golden Eagle Festival.

Still, Kaehler hopes that the growing popularity of the festival — which he describes as one of his “best trips in the past 20 years” — doesn’t have the effect of diluting the culture it was meant to preserve.

“I think it would be good if more people saw it, as long as it doesn’t get too commercial,” Kaehler said. “Some people make a living by bringing people there, like me. We still have a low profile, but hundreds of tourists are coming.”