“They rarely, or ever remain in one place more than thirty days; but ever, as though bearing God’s curse with them, after the thirtieth day, go like vagabonds and fugitives from one locality to another, in the manner of the Arabs, with small, oblong, black, low tents, and run from cavern to cavern, because the place where they establish themselves becomes in that space of time so full of vermin and filth that it is no longer habitable.”

This was the first written account in Western Europe of the people who would come to be known as Gypsies, or Romani. Over the next four centuries, these people, who began their journey in northern India a thousand years prior, would cross every kingdom and principality in Europe. By the 18th century, they had traveled to America, and today they live all over the world.

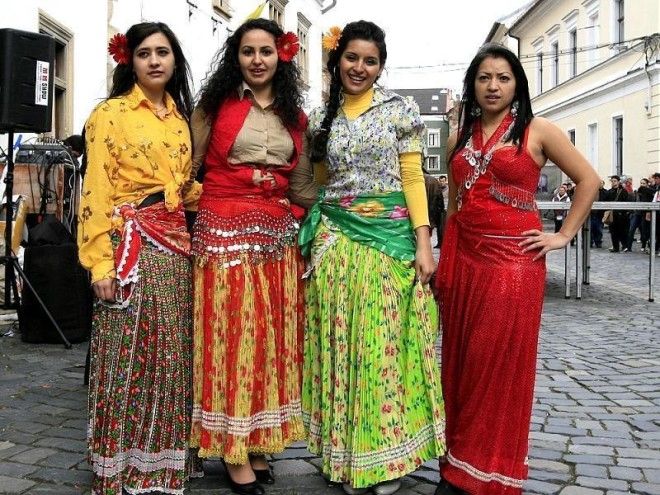

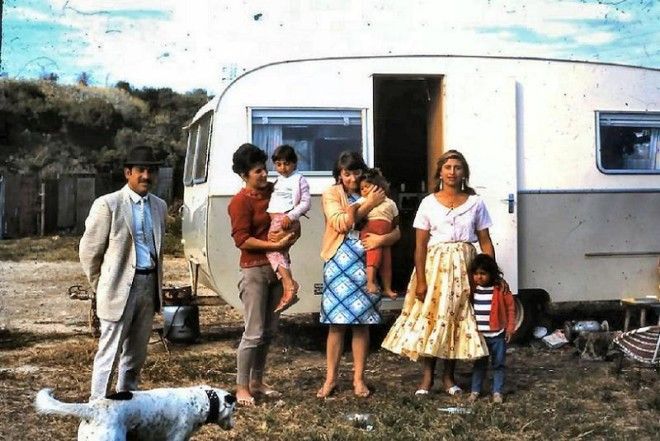

Some Romani still live in the traditional manner–migrating from place to place, always staying outside of cities–while others have joined the larger society around them. In every place they’ve ever lived, the Romani have taken up local languages and religions, married into the local population, and somehow retained their distinct identity.

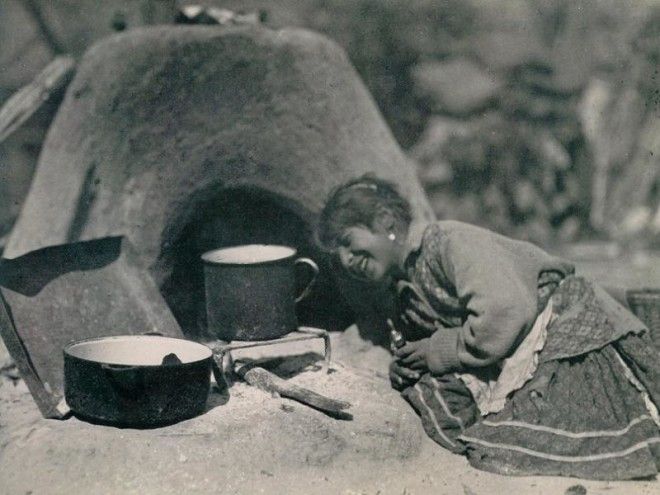

This has been both a blessing and a curse, as the Gypsies’ place in society has oscillated from “tolerated” to “actively persecuted.” Nevertheless, it seems 16 centuries of history are difficult to completely erase, and the ancient lifestyle survives to this day:

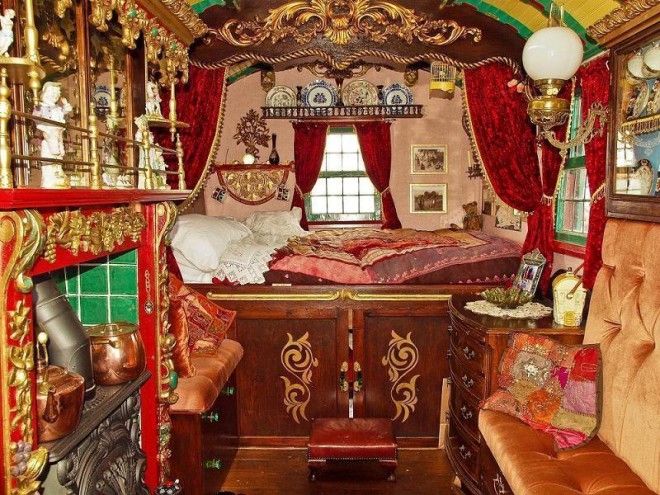

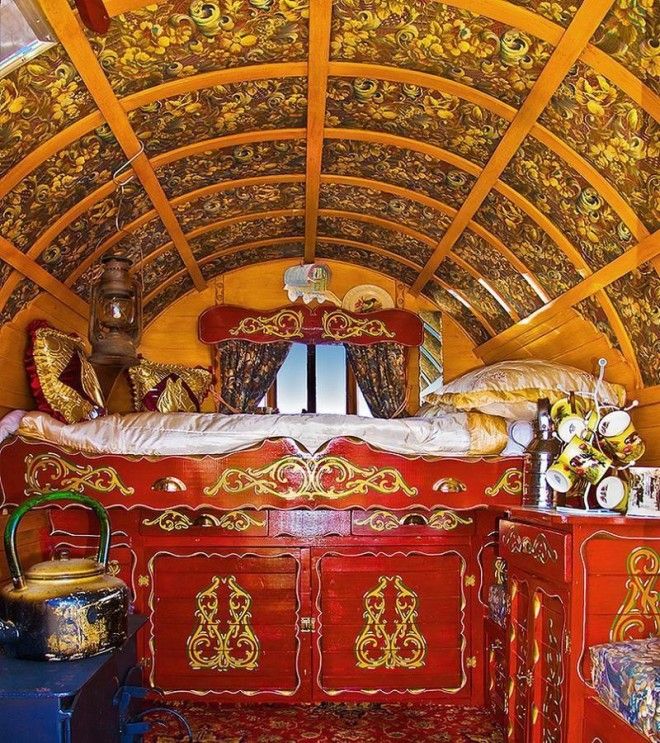

This is the sort of thing most people imagine when they think about Gypsies. Wagons like this carried the first wave of Romani migrants out of India as early as the fifth century AD. Horses pull these wagons, which are capable of crossing steppes, rivers, and mountain ranges at about the speed a person can walk.

The interior of a wagon is just as busy as the exterior.

In the 800 years that the Romani have been present in Europe, many have given in to the temptation to settle down and live more sedentary lives. As early as the 1360s, land was being granted to Romani who were willing to settle on Corfu.

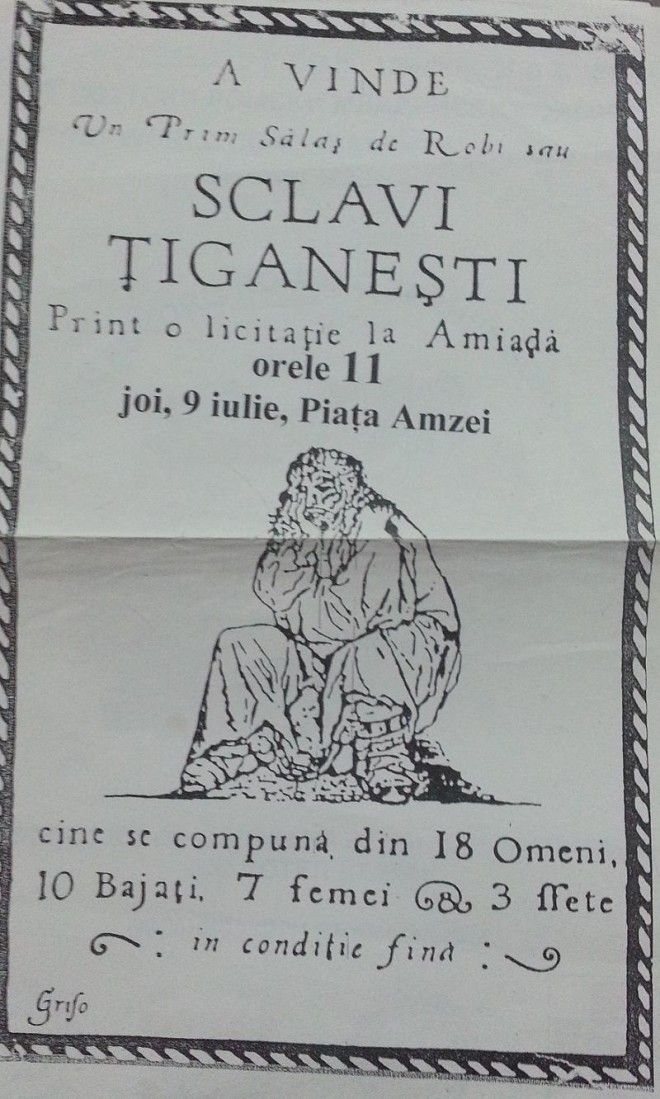

This didn't always work out well. The first recorded Gypsy slave auction took place in Wallachia, in the late 14th century. This poster, advertising another auction, is from 500 years later.

A Gypsy slum in Belgrade.

To make ends meet, or just to manage the financial death-spiral, many European Gypsies took to putting on traveling shows and spectacle-oriented gimmicks for the money bored townspeople would pay to be entertained in the long, dark centuries before the invention of TV. Soon, Gypsy communities had gained a reputation for being hotbeds of fortune-telling, kidnapping, and thievery.

The persecution began early, and it was a rare part of Europe that didn't enforce anti-Gypsy laws with extreme harshness. The Gypsies who reached Western Europe in the 15th century were mostly refugees from Ottoman persecution, but local populations in Germany and France assumed they were spies for the Turks. In the mid-18th century, the Spanish government rounded up the Romani and deported able-bodied men to forced labor camps. Around the same time, Austria outlawed the ownership of wagons and the speaking of the Romani language. Punishment for noncompliance ranged from whipping to death.

Unlike the Jewish pogroms, persecution of the Gypsies usually had no religious angle. By far, the majority of Gypsies in Catholic countries follow the Catholic faith, as is the case with this group, shown during a pilgrimage. In Orthodox countries, they follow the Orthodox Church. The same pattern can be seen in majority-Muslim countries, and even among Anglican and Pentecostal communities in England and Portugal, respectively. With Gypsies, the suppression and expulsion orders were pure ethnic cleansing.

Advertising

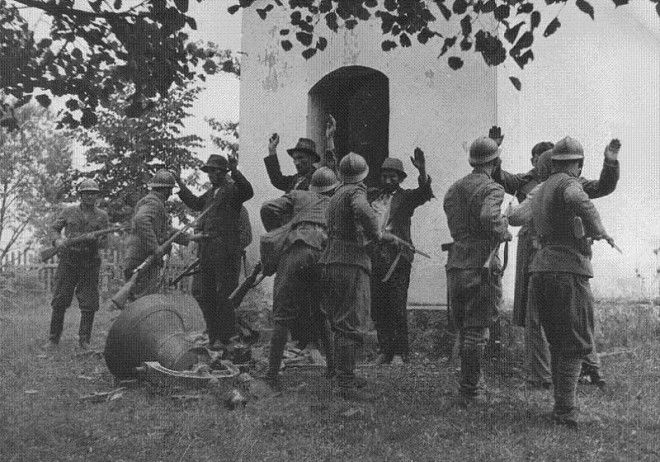

As early as 1510, Swiss law imposed death on any Gypsy found within the country's borders. From 1554, the rule was applied to England. Another order of death was issued in Denmark in 1589. In 1538, Portugal began a series of deportations to Bahia, Brazil, and other overseas possessions, where the Inquisition often followed the hapless Gypsies. In 1880, Argentina became the first New World country to block further immigration. In 1885, the United States followed suit. In 1896, Norway passed a law authorizing the forced removal of Gypsy children. Perhaps 1,500 children were taken under this law and raised in orphanages. In the above picture, soldiers arrest Romani men in occupied Yugoslavia.

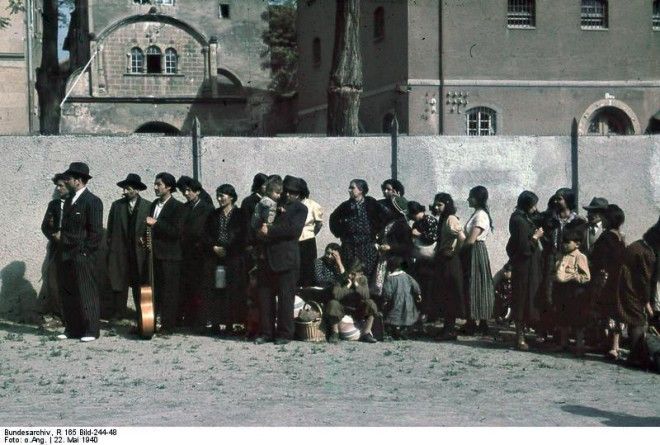

In this picture, taken in 1940, the Romani of Asperg, Germany are held awaiting deportation. The 1935 Nuremburg Laws had dealt with Germany's Gypsies on much the same terms as the Jews. Eventually, facing the extreme difficulty of arresting itinerant travelers, the Wehrmacht and SS adopted a shoot-on-sight policy for Eastern Europe's Romani.

Here, German Dr. Robert Ritter conducts an interview with a Gypsy woman. Ritter was a "specialist" in "Gypsy psychology." We leave it to your imagination what kind of bilge he published about the subject.

Ritter again. It isn't known how many Romani died during the Porajmos, which is the name given to the Nazis’ attempted extermination of the Romani, but it certainly wasn't less than six figures. Death estimates range up to 1.5 million people, though the Gypsy lifestyle makes an accurate census virtually impossible. Many of those shot simply went unrecorded, as they had no official existence to begin with. Bohemian Romani, the dialect spoken in Czechoslovakia, went extinct during this period. Incidentally, the war crimes case against Ritter was dismissed in 1950 for lack of evidence. He died less than a year later from natural causes.

Nobody knows how many Romani live around the world today. As befits urban nomads who take a perverse pride in being independent and hard to corral, estimates of current Romani numbers randomly shift between 2 and 12 million.