While this new study focuses on microorganisms, it’s also reminded everyone that of those trillion-plus species, Earth contains about 8.7 million complex lifeforms of the group that includes plants and animals — and that 86 percent of that group has yet to be identified by science.

Refining the lens even further, we must remember the epochal 2004 Nature report, which found evidence that primitive, hobbit-like people (Homo floresiensis) distinct from Homo sapiens lived on Indonesia’s Flores Island as recently as 12,000 years ago, a blink of an eye as far as the planet is concerned.

Upon publishing the report, Nature editor Henry Gee wrote, “The discovery that Homo floresiensis survived until so very recently, in geological terms, makes it more likely that stories of other mythical, human-like creatures such as yetis are founded on grains of truth.”

Indeed, no other human-like creature has captivated the human imagination quite like the Yeti. And while no definitive proof of its existence has emerged, the fact that there are so many species yet to be uncovered gives Yeti believers plenty of hope.

In the meantime, they’ve got this Yeti evidence to contemplate, and more coming on Animal Planet’s Yeti or Not, premiering Sunday, May 29, from 9-11PM ET/PT.

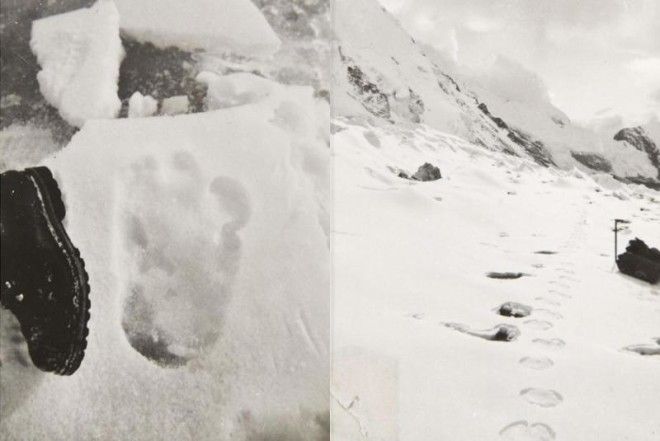

The Shipton Footprints

Alleged Yeti footprints photographed by Eric Shipton in the Menlung Basin, Nepal, 1951. These photographs sold at auction in 2014 for almost $12,000.

Although Yeti research has been marked by several high-profile claims and reports over the past few years, the golden age of Yeti research most likely remains the 1950s. And that golden age likely began with the Shipton footprints.

As interest in summiting Everest peaked in the years following World War II, the British led a reconnaissance expedition up the mountain in order to scout out plans for a future ascent to the very top.

That 1951 trek was led by British mountaineer Eric Shipton. As Shipton and his partners reached Menlung Basin, about 16,000-17,000 feet above sea level, they came across a long series of footprints.

At 12-13 inches long yet twice the width of an adult man’s foot (and with unusual toes), a depth suggestive of weight greater than a man’s, and claw marks nearby, these footprints almost certainly weren’t human.

Fortunately, Shipton photographed the prints. Two days later, the prints were wiped away by sun and wind — and with them the world’s first great piece of Yeti evidence.

The Khumjung Scalp

The alleged Yeti scalp of Nepal’s Khumjung monastery, introduced to the Western world by famed explorer Edmund Hillary. Nuno Nogueira/Wikimedia Commons Two years later, building upon Shipton’s reconnaissance, Edmund Hillary of New Zealand and Nepalese Sherpa Tenzig Norgay completed what is perhaps history’s greatest feat of exploration when they became the first people to summit Everest.

But while Hillary’s mountaineering is known the world over, few realize that he was also, for a time, one of the world’s foremost Yeti hunters.

In the course of Hillary’s historic ascent, he claims to have spotted mysterious footprints in the snow on the Barun Khola mountain range, which Norgay believed came from a Yeti. However, unlike Shipton, Hillary didn’t photograph them, leaving that alleged Yeti evidence (along with the Yeti hair he’d supposedly found in the Himalayas the year before) lost to history.

In 1960, Hillary launched a full-fledged Yeti hunting expedition into the mountains of Nepal. While there, Hillary and his team visited a monastery in the village of Khumjung. There they acquired a purported Yeti scalp that had been in the village’s possession for over 200 years.

Upon Hillary’s return to London, the world was abuzz at this incredible piece of Yeti evidence — only to be let down after scientists quickly found that the “scalp” was actually the hide of a serow goat.

The “scalp” has since returned to the monastery, where it remains to this day.

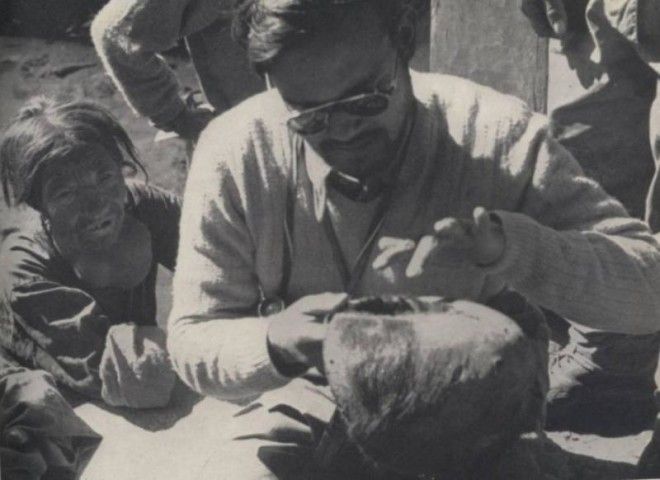

Yeti Evidence: The Pangboche Scalp

Dr. Biswamoy Biswas examines the alleged Yeti scalp uncovered at the Pangboche monastery during the 1954 Daily Mail expedition. John Angelo Jackson/Wikimedia Commons In 1954 — one year after Hillary reached Everest’s summit, and near the height of Yeti mania — Britain’s Daily Mail financed a major expedition to Nepal in search of Yeti evidence. While the team claimed to have found a number of compellingly unidentifiable footprints, their most dramatic find was the Pangboche scalp.

Much like the Khumjung scalp, this one was found at a monastery in the village of Pangboche. Its hairs, ranging from black to brown to red, were analyzed using microscopes and microphotography, then cross-referenced with samples from known animal specimens including bears.

Advertising

After completing this analysis, British scientist Frederic Wood Jones was unable to identify the hairs’ origins — leaving believers with plenty of room for hope.

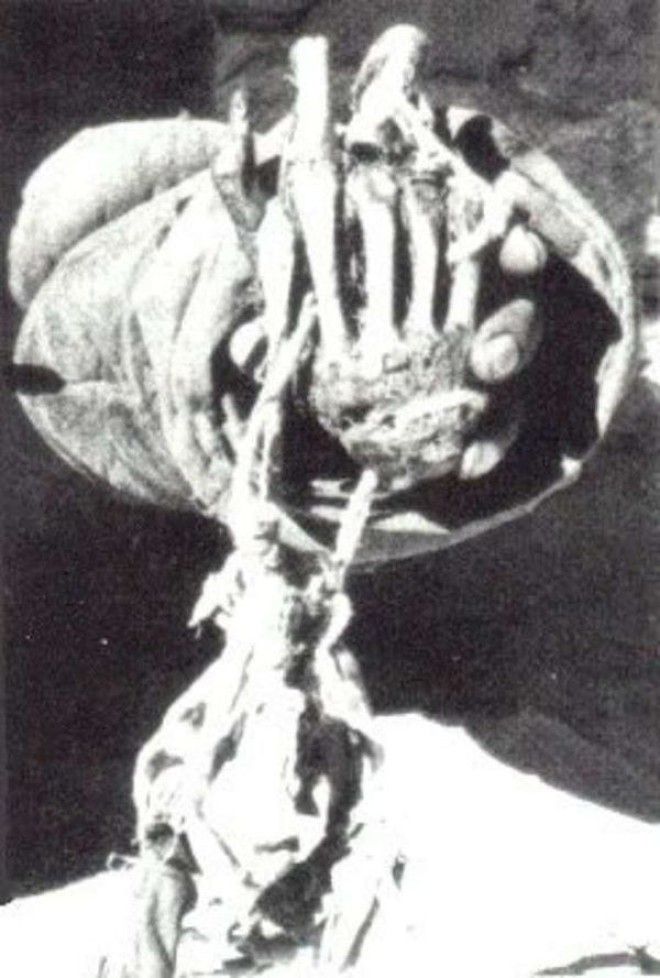

The Pangboche Hand

The Pangboche hand, once believed to be that of a Yeti, as photographed by Peter Byrne, one of the explorers who found it, in 1958. Peter Byrne/Wikimedia Commons Even for a Yeti story, the true tale of the Pangboche hand is almost too fantastical to believe.

Having heard rumors of a Yeti hand housed in the same town that held the Pangboche scalp, American oil man and Yeti hunter Tom Slick asked explorer Peter Byrne to go to Nepal and retrieve it.

When the temple custodians told Byrne he couldn’t have the hand, he returned and gave his employers the bad news. Instead of calling it quits, Slick and partner Osmond Hill hatched a new plan: Send Byrne back to Nepal to steal a finger from the Pangboche hand and replace it with a human finger.

Over lunch with Byrne at a London restaurant, Hill took out a brown paper bag and tilted it over the table. A human hand spilled out. “It was several months old and dried,” Byrne told the BBC decades later. “I never asked him where he got it from.”

Then, back in Nepal with the human hand in tow, Byrne offered to make a donation to the temple (only about $160 in today’s dollars) in exchange for one finger from the Pangboche hand. He also offered a replacement human finger. The custodians accepted.

And even after all that, this is where the story fit for the movies actually brings in a movie star. Slick asked his friend, actor James Stewart (star of It’s A Wonderful Life, Vertigo and at least a dozen other classics), to help Byrne smuggle the finger to back to London, believing a celebrity could slip through customs more easily.

Stewart and his wife, Gloria, were in India at the time, and once Byrne got over the border from Nepal into India, he met Stewart in Calcutta. There, they stowed the finger in Gloria’s lingerie case and the Stewarts made it out of India no problem.

Except that when the couple arrived in London, the lingerie case was missing. A few days went by before a customs officer returned the case with the finger still inside. Of course, the customs official likely knew nothing of the finger, assuring Gloria that no British customs official would look through a lady’s lingerie.

And in an ending that’s either a total letdown or pure poetry (probably depending on whether or not you’re a Yeti believer), the “Yeti” finger for which they traded a human finger was found, in 2011, to be human itself.

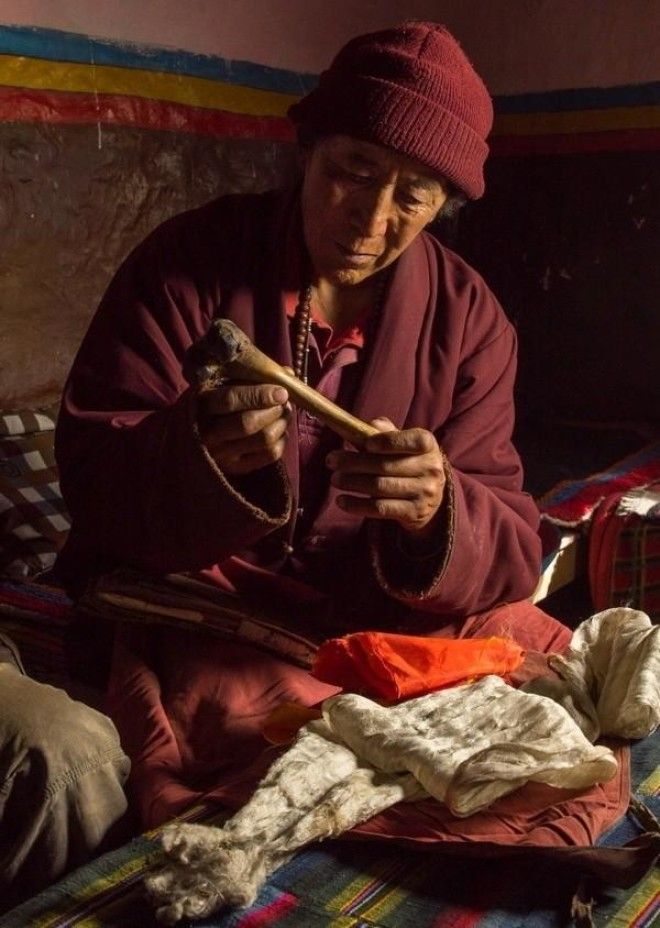

The Pemba Bone

Pemba, an Amche or traditional healer, with claimed Yeti bone in the Upper Mustang region of the Nepalese Himalayas. Animal Planet Recently, an Amche (traditional Nepalese healer) named Pemba of the Upper Mustang region of the Himalayas claimed to have found a dead Yeti in its cave. He then claims to have taken a bone from the Yeti’s right leg.

Now, celebrity veterinary surgeon Dr. Mark Evans, as part of Animal Planet’s upcoming Yeti or Not special, plans to test the bone for DNA evidence, hoping to prove once and for all that the unbelievable Yeti does in fact exist.