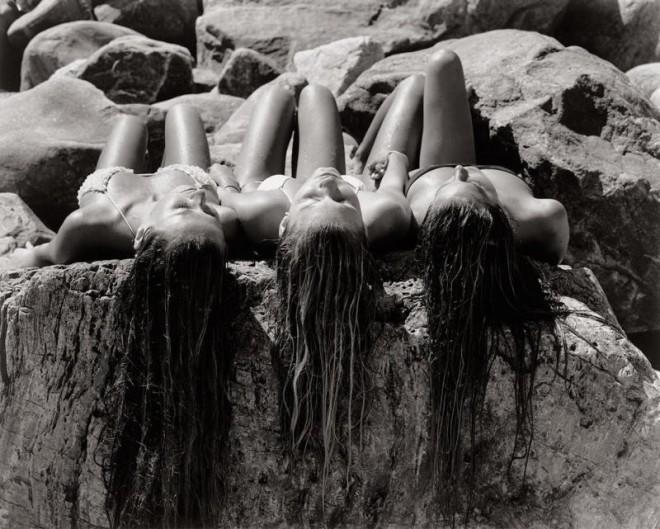

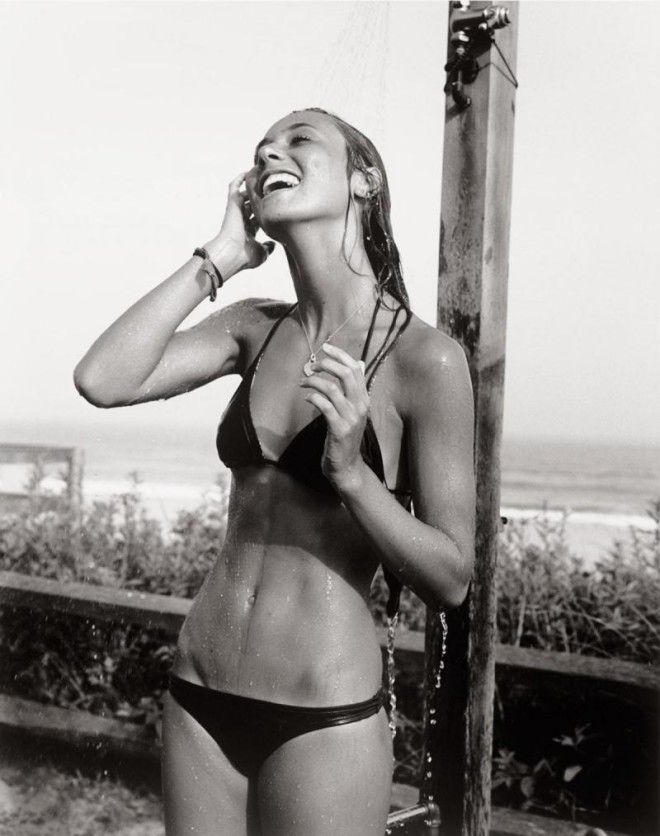

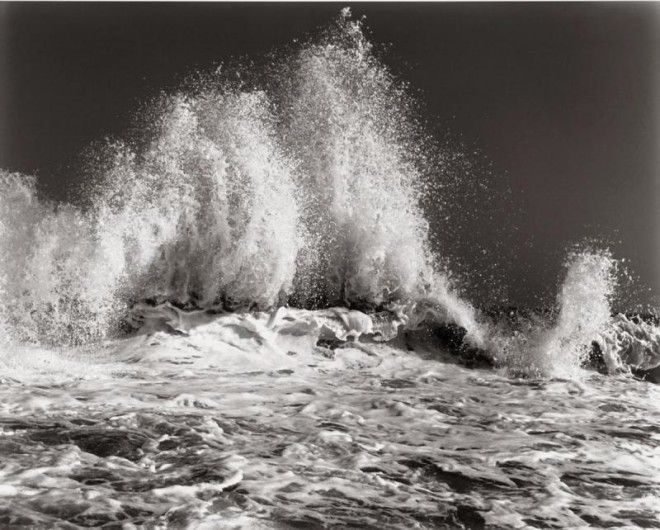

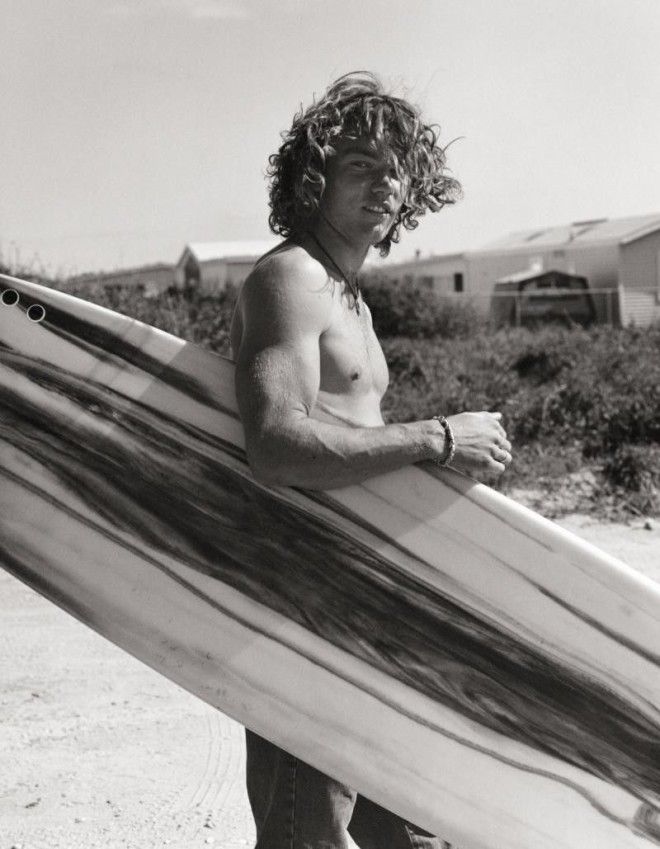

What Dweck discovered instead was a beautiful surf town that would serve as his muse for years to come.

As a professional photographer, it was natural for Dweck to begin documenting the surf culture of Montauk when he officially moved there in 2002. His images, captured in the summer of 2002, were published in the book "The End: Montauk, NY."

In celebration of its 10th anniversary, the book is being republished in a box set with a $3,000 price tag.

Ahead, see a selection of work from the book, as well as Dweck's recounting of the stories behind his favorite place.

Dweck grew up on Long Island and visited Montauk often as a teen. His photography has long been inspired by beach culture.

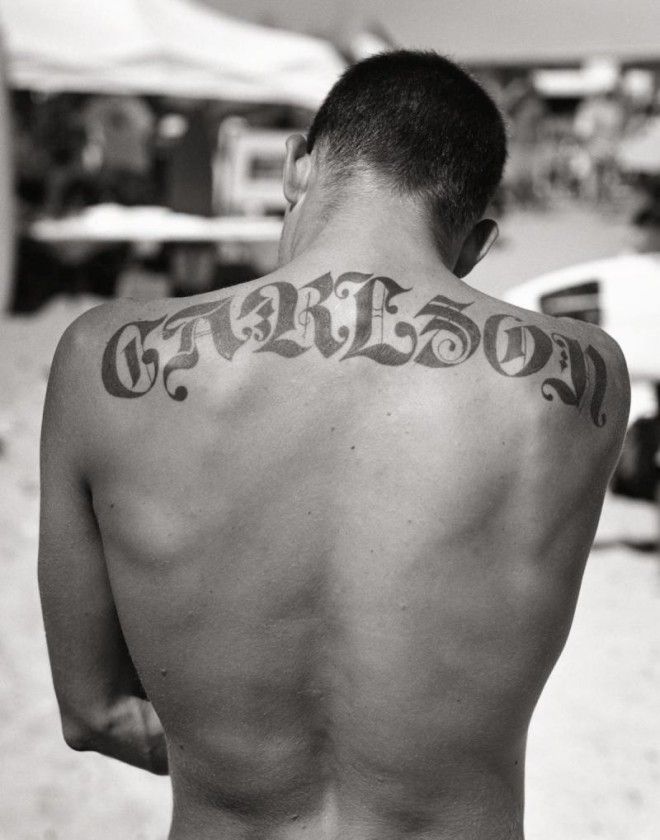

In the foreword of his book, Dweck described himself as an "outsider" in Montauk. "It wasn't that the locals were mean (although some were)," he wrote. "They just had a good thing going and they weren't keen on sharing it with the whole world."

Dweck became a true local when he moved there in 2002.

"[Montauk] was a muse before I needed a muse, before I had any project in mind, or any thesis. I was photographing for fun," he said.

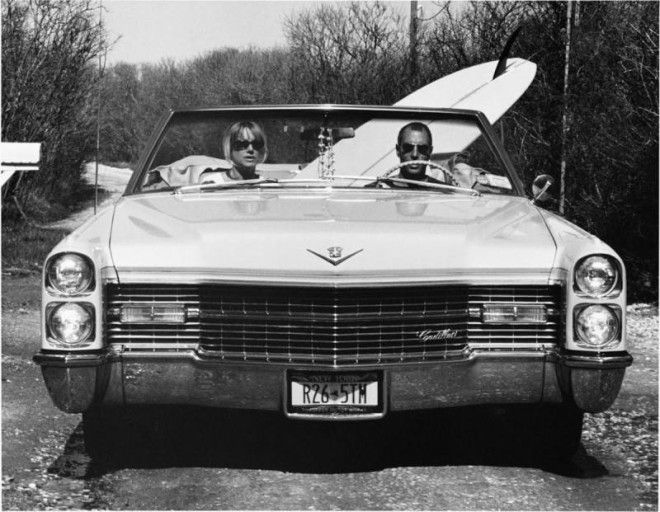

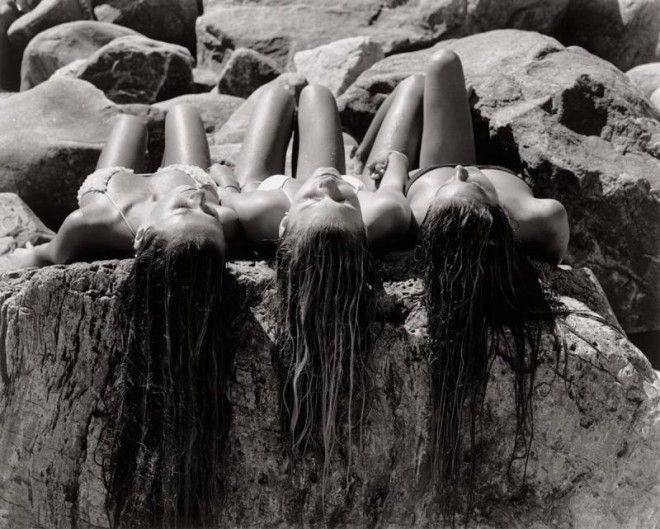

However, Dweck began to recognize that it was a pivotal time for the community. "I saw the slow change [in Montauk] — the 'Hampton-ization' coming down the pike, as it were," he said.

"'Hampton-ization' goes well beyond [an influx of] traffic and tourism. It's about community, and the casualties of these 'booms': the working-class families, the local fishing industry [and] the mom-and-pop icons," he said.

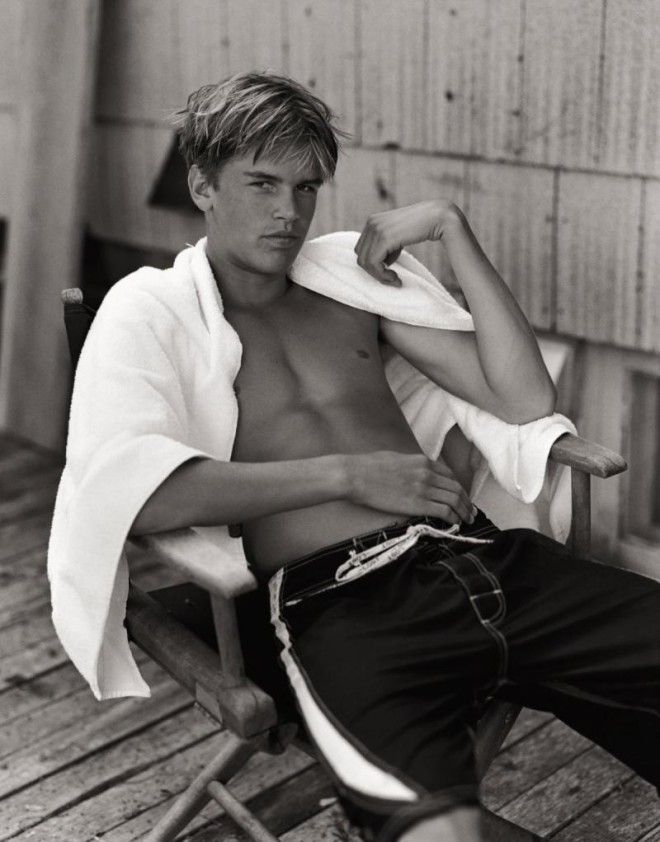

Dweck captured scenes of the town before condos and themed chain restaurants came through, effectively destroying the small-town feeling.

Dweck described Montauk during the early 2000s as "independent, intimate, and peerless."

The aim of his book was to "preserve paradise."

This goal, Dweck says, is what has made the book so successful. "Everyone has his or her idea of paradise," he said. "I meet people who have never been [to Montauk], who respond viscerally to the photographs. They're responding to the meaning of the work, where Montauk is a surrogate for their own personal paradise."

"I think the art endures because it represents an idealized sense of place, and reinforces the idea that memory — individual or communal — can make [a] place timeless," he said.

If Dweck were to create the series today, "It would be much bleaker," he said. However, "I think the heart would still be the same: to capture the perseverance and beauty of the endangered."