Each was prepared with obsessive detail to conform to company directives.

Like any business, however, McDonald’s knew when to change their corporate recipe to fit the times. Have a look at these 14 facts about the Golden Arches and their unique approach to serving fast food in the 1960s.

1. THEY DIDN’T HIRE WOMEN.

Fast-service restaurants in the ‘40s and ‘50s were renowned for their carhops—perky young women who delivered trays of food to parked automobiles. But franchise founders Maurice and Richard McDonald held a negative opinion about these jobs: They felt it created an atmosphere where families would be uncomfortable visiting a burger stand populated by obnoxious teen boys ogling employees. They eliminated the carhop position, expecting customers to instead approach windows on foot. Subsequent owner Ray Kroc held firm to the no-women policy: “We don’t hire female help,” he told the Associated Press in 1959. The freeze lasted until franchise operators began insisting on a gender-balanced staff in the mid-to-late-‘60s. Even then, Kroc ruled that female employees be “flat-chested” and not work the grill since they didn’t possess the “stamina” for such intensive labor.

2. THEY’D WASH YOUR WINDOWS.

Several McDonald’s promotions in the early 1960s promised a free windshield wash for drive-in patrons. The moment anyone pulled up, an employee would deploy a squeegee and clean the glass before an order was placed. McDonald’s offered that it was for “safety” reasons, as though people drove with such filth on their cars it impaired their driving. The fast-food-with-car-wash concept never caught on beyond weekend specials.

3. NOTHING WAS FROZEN.

Find work in a contemporary McDonald’s kitchen and you’ll probably see boxes full of trucked-in frozen French fries and hamburger patties that are sometimes kept on ice up to three weeks before being cooked.

This wasn’t always the case, though. One of the company’s most often-repeated talking points in 1960s media was the fact that everything arrived fresh to stores: meat came refrigerated and potatoes were shipped whole. Each location would have to use a peeler and slicer to prepare the fries.

Eventually, the spud-related labor began to slow down service, and Kroc began phasing out the fresh fries in 1966.

4. KITCHENS HAD VIEWING WINDOWS.

Believing families had a curiosity about the McDonald’s conveyor-belt approach to food preparation, Kroc had kitchens outfitted with 900-square-foot viewing windows. Covering the front and sides, the quarter-inch glass allowed customers to see every step of burger manufacturing. According to company vice president Don Conley, the layout allowed mothers to inspect the area for cleanliness and walk away “entranced” with the stainless-steel amenities. Dads, presumably, just wanted to see meat sizzle.

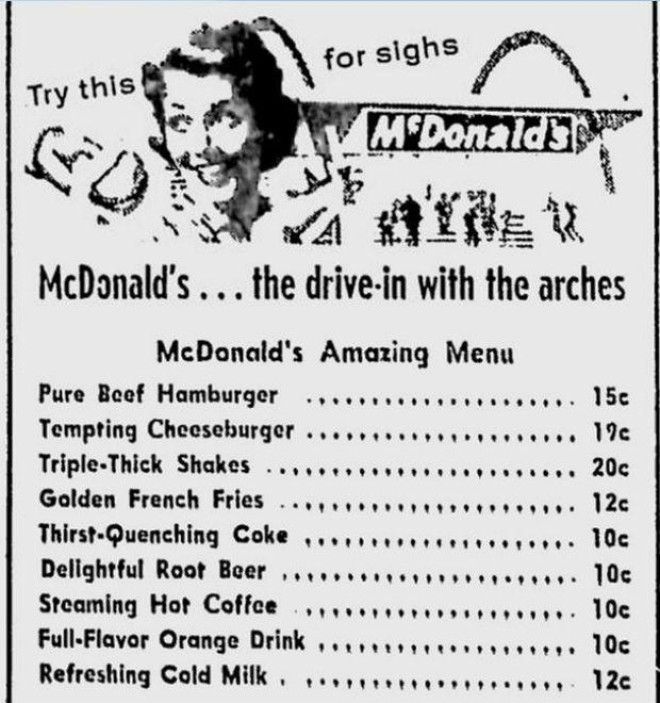

5. ENTIRE MEALS COST 45 CENTS.

A burger, fries, and shake set visitors back two quarters, with change back. The chain liked to brag that an entire nuclear family could eat there for just over two dollars.

Kroc maintained that it wasn’t food that went up in price, but the service itself. So Kroc attempted to get rid of anything that wasn't edible, telling Time in 1961, “You can’t eat a 20 percent tip." (Cow inflation did eventually set in: In 1966, the price of a hamburger rose from 15 cents to 18.)

6. THEY DIDN’T WANT BUSINESS FROM DIRTY HOBOS.

Family was a key selling point for McDonald’s. Time and again, spokespeople for the chain reinforced the idea of creating an environment parents would be comfortable in. The company told press that new locations were scouted based on the number of church steeples, schools and residential streets nearby, not foot traffic. McDonald's, Kroc said, didn’t want to cater to “transients.”

7. KIDS ATE SIX BURGERS A WEEK. THIS WAS A GOOD THING.

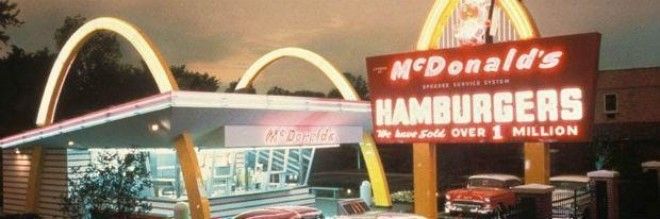

Statistics were a big part of the McDonald’s corporate message when the company began moving across the country. They estimated roughly 800 million burgers were sold by 1963; 460 stores were operating in 42 states that same year. They also liked to brag that kids had become burger-munching maniacs, telling press that children devoured 6.2 of them per week in 1966.

8. THEY BANNED CIGARETTE MACHINES AND JUKEBOXES.

Continuing their bid to oust delinquents and miscreants from the premises, Kroc mandated that no location would install a jukebox, cigarette machine, or phone booth. (The jukebox ban was part of his “three nos” campaign, which also included no tipping and no carhops.)

9. YOU COULDN’T SIT DOWN.

With an average transaction time of just 50 seconds, McDonald’s didn’t really have the time or resources to put into washing dishes. Virtually all locations in the early ‘60s amounted to front counters and drive-in windows: There was no place to sit down inside the restaurant itself until 1962, when a Denver, Colo. location became the first to offer stools.

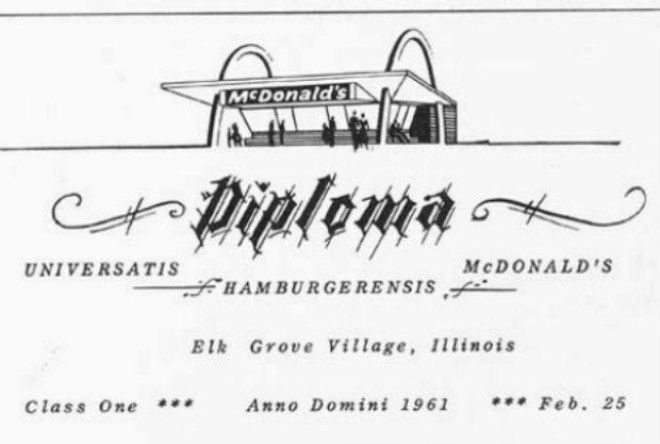

10. THEY INTRODUCED HAMBURGER UNIVERSITY.

Franchisees looking to get in on the near-guaranteed cash cow that was a McDonald’s location needed $12,000 in franchise fees and deposits, and then they would pay 2.2 percent of sales back to McDonald's. They also needed to spend time at Hamburger University in Elk Grove, Ill., where they’d receive a crash course in everything from restaurant management to pickle distribution. Opening in a restaurant basement in 1961, the school offered majors in “hamburgerology” and minors in fries. Accomplished students could graduate “magna cum mustard.” 500 people attended each year.

11. THEY HAD (LOCAL) CELEBRITY APPEARANCES.

Before the rise of Ronald McDonald, McDonald’s took a homegrown approach to in-store appearances. While kids begged parents to let them see such luminaries as Zorro and Uncle Ben, the chain also promoted appearances by regional kid show personalities like Quacky the Ducky, Miss Ann, and Mr. T. (Not that one. Another one.)

12. KROC DIDN’T WANT A “STINKY” FILET-O-FISH.

McDonald’s now boasts an expansive, two-sided drive-thru menu, but there was a time when they bragged about keeping options capped at 10 items or less. It was Monfort, Ohio franchisee Lou Groen who opened the doors for the McNuggets, Big Macs, and other innovations to come. In 1961, he presented Kroc with the idea for a fish sandwich, which he wanted to introduce to bolster his business during Lent. Kroc was unimpressed, telling Groen he didn’t want stores smelling like seafood. The two eventually agreed on a test market run; the halibut-based sandwich proved to be a hit. McDonald’s now moves more than 300 million of them every year.

13. FRED TURNER WAS THEIR SECRET WEAPON.

Turner originally wanted to be a franchisee until he lost his financial backing. Going to work for corporate, he became a master of efficiency. It was Turner who would figure out how many burger patties could be piled up before falling over, and that stores could save precious seconds if buns came to them fully separated instead of only partially halved. In 1977, Turner became CEO.

14. THE ARCHES WERE SUPPOSED TO MAKE YOU THINK OF BREASTS.

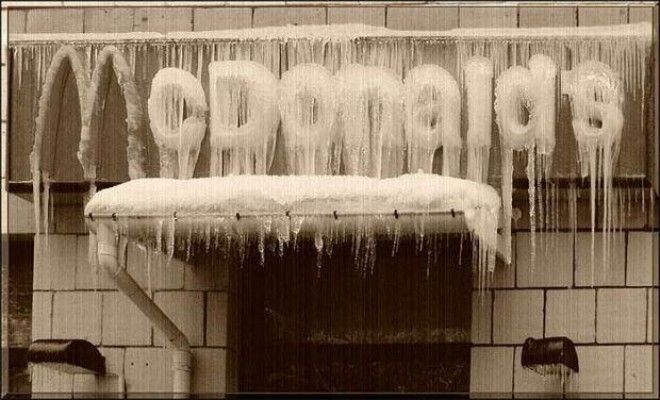

While the Golden Arches that formed a swooping “M” were part of McDonald’s architecture that made stores easily recognizable, at least one advisor thought they served another purpose entirely. According to the BBC, psychologist Louis Cheskin convinced the franchise to keep the logo in the 1960s because of the “Freudian symbolism of a pair of nourishing breasts.” The company wound up taking Cheskin’s advice.

Despite remodeling their storefronts, the arches stayed.