Before our current processes became commonplace, many radical methods were used to treat patients regarded as “mad,” which included everything from drills to purges to religious rituals. Let’s take a journey back in time and explore the antiquated ways our ancestors sought to help their fellow man…

Trepanation

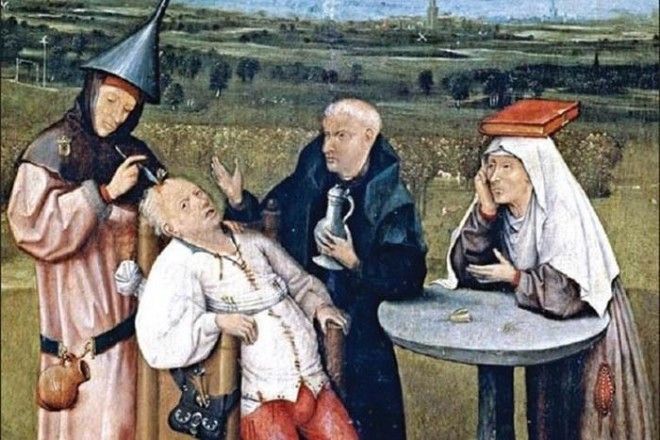

A painting depicting trepanning.

Even in the Stone Age, primitive peoples were able to recognize mental illness, though their method of dealing with it was as far from our current ways as their culture is from ours. In short: they would cut holes in each other’s heads.

This “treatment” was used all over the globe, with the manner of cutting ranging from using stone knives, to cutting the bone in a circle and then lifting the disc away, to drilling a circle of holes placed close together and then cutting in between them. The skull would be penetrated, but the the membrane surrounding the brain would be left intact.

Trepanning was used to treat insanity, epilepsy, melancholy, and any number of other mental ailments, but the common theme of the procedure seems to be that cutting a hole in the head would release evil spirits and relieve the patient of their anguish. Sometimes, the piece of bone was given to the afflicted person or their family afterward, as a talisman.

Astonishingly, the practice continued until as recently as the 18th century, when it was finally given up as the mortality rate hovered somewhere around 25%. Even today, any type of psychosurgery is considered to be experimental and not to be taken lightly. The chances of drilling a hole in someone’s head with stone tools to release the demons inside being a successful method of treatment? Slim to none.

Exorcism

Exorcisms were believed to cast madness-causing demons outside of the body.

Since 3000 BCE, in the time of the Babylonians and Egyptians, some people considered to be “mentally abnormal” were thought to be plagued by demons. Indeed, between the years 200 and 1700, almost all mental illnesses were considered to be caused by possession. However, instead of cutting into people’s heads to let the bad spirits out, exorcism was used instead.

In Mesopotamia, priests used religious rituals to cast the demons out, and by the Middle Ages, the steps of an exorcism were clearly delineated. First, a priest would try to coax the demon out. If that didn’t work, they would insult the demon. If the ritual was still unsuccessful, the possessed person would be made so physically uncomfortable (i.e. immersed in hot water or subjected to sulfur fumes) that the demon would not want to stay within them.

However, whether or not an exorcism works seems to depend solely on the attitude of the possessed person. If they believe themselves to be possessed, and that an exorcism will help them, it probably will. As for a long-term solution? Unless the patient is willing to use exorcism like continuous therapy, it’s doubtful that they’ll remain “cured.”

Art Therapy

A depiction of art therapy in ancient Egypt.

Not all historical treatments were quite so radical, and some even touched on aspects of what we currently practice today. The ancient Egyptians, for example, recommended painting, dancing, and attending concerts to relieve symptoms of mental illness. In Babylon, Assyria, and the Mediterranean, music was used in the hope of curing the mentally ill, as they felt it affected emotion (and rightly so).

During the Renaissance and after, artists were considered to be people safe from mental illness; art was considered to be a form of therapy that allowed for the purging of things that might otherwise lead to madness.

Even during the Industrial Revolution, some mental health patients were treated with “moral therapy,” which interestingly enough, had absolutely nothing to do with morals.

Advertising

Instead, people were taken to the countryside, where they engaged in artistic pursuits to ease their troubled minds. This is actually one of the best treatments that the ancients could have used. Art therapy has been proven in modern times to reduce levels of depression and anxiety, and improve quality of life. While there may not be ancient medical journals detailing the results of the time, the fact that art therapy has lasted so long as a treatment — and is still considered effective today — suggests its value as a treatment.

Bloodletting

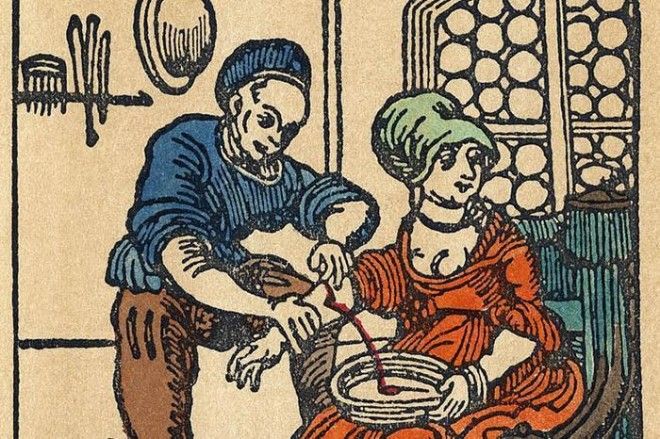

A depiction of bloodletting.

Bleeding a patient to cure mental illness began around the time of the ancient Egyptians (because art therapy can’t cure everything), and then was taken up by the Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Asians, and eventually Europe, reaching its peak usage around the 19th century. The Greek rationale was that, in order to keep the four humors in balance, getting rid of “bad blood” would restore someone to health, and other cultures followed suit with this line of thinking.

The median cubital vein (the one at the elbow where IVs are often placed now) was often used for bleeding, and cuts were made with lancets (small, pointed knives that could be carried in a doctor’s pocket) or a fleam (a device much like a Swiss army knife, with multiple-sized blades that could be folded up).

Leeches were also used, though their placement depended on the area where the physician determined the cause of the illness to be. We have discovered in modern times that while leeches can be used effectively in some skin and musculoskeletal disorders, using them for mental illness to balance the “four humors” has no merit. Likewise, bloodletting seems to have no practical application today, which goes to show that the people of yore lost a good deal of blood and gained back none of their sanity.

Purges

A depiction of a purge.

Around the same time as bloodletting was being explored, physicians began to think that the cause of mental illness lay within a patient’s body, and could be cured by expunging it through pretty disgusting means.

One of the most common treatments was to induce vomiting. Ancient Greeks used black hellebore, a bad tasting though beautiful flower. Bitter apple was also used for its bad taste, and Americans used tobacco. The Arabs made a concoction of myrobalans (an astringent plant), rhubarb, and senna, which has laxative properties, to clear the bowels.

Apparently these purges were meant to clear people of melancholy, however the process itself would seem to induce a melancholic state, rather than cure one. Indeed, since the process had the same rationale as bleeding, purging in any fashion is just as ineffective as bleeding — and just as unpleasant.